The Supreme Court’s Article 370 Judgment: On Representative Democracy – A Comparison with Miller 1

[This post first appeared as a guest post on the blog, Indian Constitution Law and Philosophy]

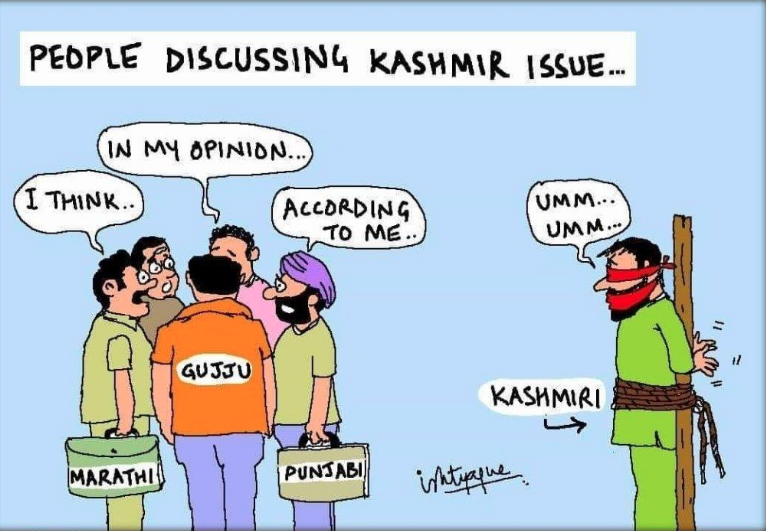

The critical question in In re: Article 370 of the Constitution was whether the President (acting on advice of the Government of India) could terminate Article 370, without involving the representatives of the people of Jammu & Kashmir (‘J&K’). This obligation to involve the representatives of the people of J&K arose because of the proviso to Article 370(3). According to the proviso, a recommendation from Constituent Assembly of J&K was a pre-condition before the President issued a notification to terminate operation of Article 370.

Conceptually, a similar question arose in the United Kingdom (‘UK’) in 2017 in R v. Secretary of State for Existing European Union (‘Miller 1’). Article 50 of the Treaty on the European Union (‘EU’) provided that a member state could withdraw from the EU after complying with its own constitutional requirements. The question in Miller 1 was whether the Government of UK could unilaterally withdraw from EU in exercise of its prerogative powers or whether it had to obtain the approval of the representatives of the people of UK in the Parliament.

Thus, fundamentally, the question in both In re: Article 370 and Miller 1 was whether the executive was legislatively constrained from exercising power. In this post, I compare these two judgments. As we shall see, the judgments reveal the constitutional values the courts embrace. While the Supreme Court of India continued its practice of deferring to the executive at the cost of the legislature, the majority opinion of the Supreme Court of the UK restrained the executive from depriving people of domestic rights without parliamentary approval. The argument is not that the Supreme Court of India should have followed Miller 1 – it could not have, considering the difference in the constitutional schemes and the specific questions before them. Instead, it is to highlight which values each of the courts placed a premium upon.

Beyond this critical question, I also compare how the two courts responded to similar assurances by the executive that the legislature will enact legislation at a later date. While the Supreme Court of India readily accepted this submission and chose not to decide on the legality of converting the State of J&K into a Union Territory, the Supreme Court of United Kingdom, outrightly rejected it.

On the critical question

The question before the Court in In re: Article 370 was whether Constitutional Order (‘CO’) 273 complied with the procedure provided in the Constitution. Kieran Correia, in a previous post has explained the import of the CO. For our purposes it is enough to say that CO 273 notified that Article 370 shall cease to exist. It was issued under Article 370(3), the proviso to which, required a recommendation from the Constituent Assembly of the State. The purpose of the proviso was to uphold the fundamental character of representative democracy (See Mohd. Maqbool Damnoo v. State of Jammu & Kashmir). The President could not alter Article 370 without involving the direct representatives of the people of Jammu & Kashmir.

The Supreme Court did not dispute this position of law (See Para 426). Yet it upheld CO 273, even though the representatives of the people of Jammu & Kashmir did not have any say in its notification. The justification offered by the Court was that since a) the Constituent Assembly had ceased to exist, the President could unilaterally notify that Article 370 shall cease to operate; and b) the recommendation was anyway not binding on the President (para 346). As Kieran has pointed out, the first justification ignores that the proviso to Article 370(3) indicates ‘more than the Constituent Assembly as an institution, it is the constituent power of the people of Jammu and Kashmir that was represented.’ The second justification sidesteps the text of the Constitution which made recommendation from the representatives of the people a pre-condition before the exercise of executive power. It does not matter that the recommendation was not binding: the fact of the recommendation was still necessary.

How does this compare with the majority opinion in Miller 1? As mentioned above, the question in Miller 1 was whether the Executive in the UK could unilaterally initiate the process of leaving EU without parliamentary approval. The Executive in the UK has a prerogative power to enter into and withdraw from treaties. Despite acknowledging the centrality of this prerogative power in the constitutional scheme of UK, the Court held that parliamentary approval was necessary. The majority observed that ‘far-reaching change to the UK constitutional arrangements’ cannot be brought by ministerial action alone. The change was far-reaching because withdrawal from the EU would abrogate the rights available to people in the UK from EU law (para 81). These rights were created by a series of statues which the Parliament had enacted after the UK joined the EU. Therefore, parliamentary sovereignty required that only the Parliament could take away those rights, and not the executive.

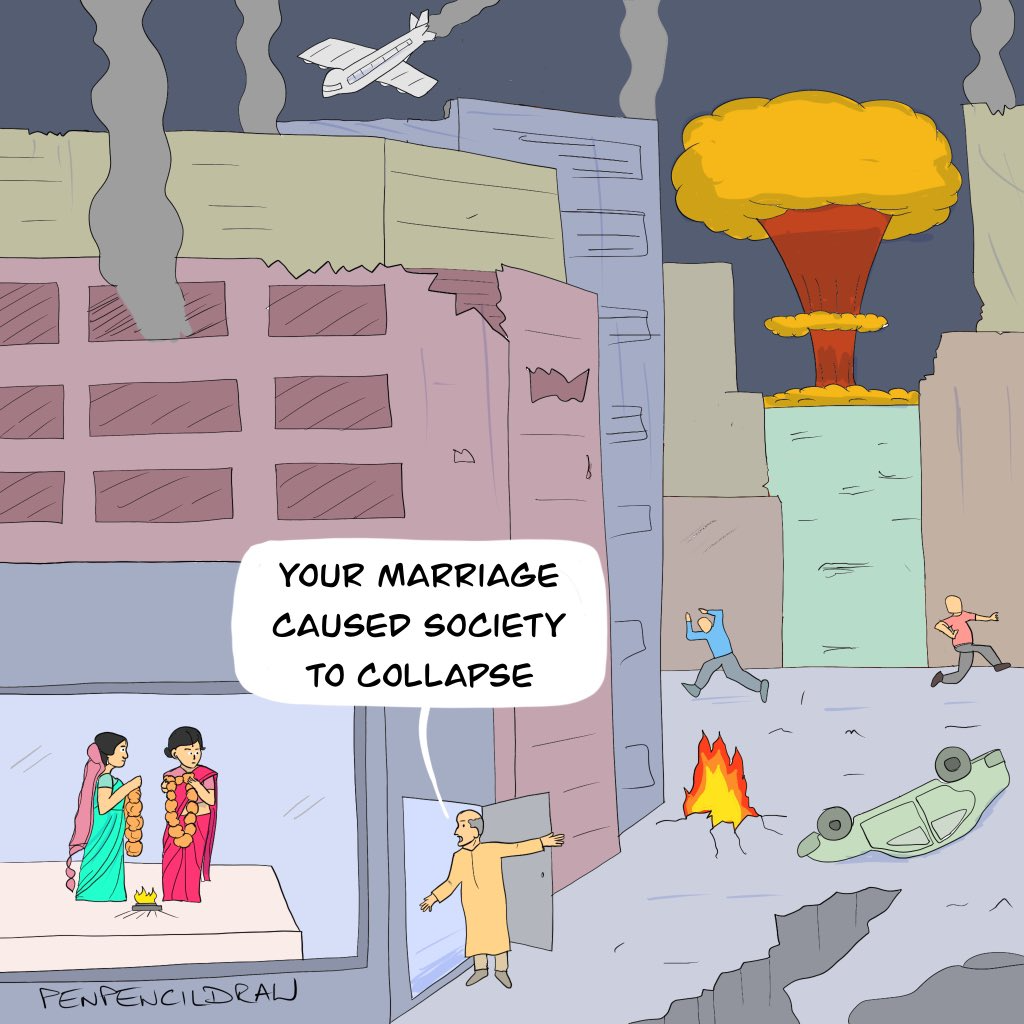

Thus, the decision in Miller 1 placed a premium on the legislature, as against the executive. This was consistent with the principle of representative democracy. In contrast, the plurality opinion in In re: Article 370, crowns the executive with a power greater than what the executive itself claimed. The executive believed that a recommendation from the Parliament (and not the Constituent Assembly) was necessary, but a deferential court held that the executive could unilaterally cease the operation of Article 370. This approach which side-lines the people of Jammu & Kashmir entirely despite the explicit stipulation in the Constitution, undermines representative democracy and federalism, both of which are essential to our constitutional scheme.

On assurance

Supreme Court of India’s deference to the executive did not stop here. Another issue before the Supreme Court of India was the validity of the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019. The Act reorganises the State of Jammu & Kashmir into two Union Territories. The Petitioners argument was that the Parliament cannot use Article 3 to extinguish the character of statehood by converting a State into a Union Territory. The plurality opinion waxed eloquent for 32 paragraphs (Para 471 to 502) on the constitutional history of States and Union Territories, the reason for existence of Article 3, federalism and representative democracy. However, in the 33rd paragraph, it refused to decide the legality of the reorganisation. It did so because the Solicitor General had submitted that statehood would be restored in Jammu and Kashmir (Para 503).

‘The Solicitor General (for the Union of India) submitted that statehood will be restored to Jammu and Kashmir and that its status as a Union territory is temporary. The Solicitor General submitted that the status of the Union Territory of Ladakh will not be affected by the restoration of statehood to Jammu and Kashmir. In view of the submission made by the Solicitor General that statehood would be restored of Jammu and Kashmir, we do not find it necessary to determine whether the reorganisation of the State of Jammu and Kashmir into two Union Territories of Ladakh and Jammu and Kashmir is permissible under Article 3……‘

There are two concerns. First, what may or may not happen in the future does not change the question before the Court. The question before the Court was the legality of a reorganisation which has deprived a people of a democratically elected government for the past 4 years. If the reorganisation is illegal, the illegality should cease immediately and not at an undetermined time in the future. This is akin to detaining someone illegally and then a court ruling that it will not decide the legality of the detention as the detainee will be released sometime in future.

Second, restoring Jammu and Kashmir’s statehood would require legislation from the Parliament in terms of Article 3 of the Constitution. In law or in fact, a law officer simply cannot give any assurances regarding how the Members of Parliament would vote on a bill. The Members, including those from the treasury bench, are entitled to vote as they deem fit notwithstanding the 10th Schedule. Moreover by June next year the 18th Lok Sabha will get elected and it may not have the same composition as the 17th Lok Sabha. Here, as Apar Gupta pointed out, the decision in Shreya Singhal v. Union of India, is worth noting. In that case, the validity of Section 66A of the Information Technology Act, 2000 was under challenge. The law officer for the government assured the Supreme Court that the government would not use Section 66A to curb free speech. The Court rejected the submission and held that if Section 66A was otherwise invalid, it could not be saved by an assurance which does not even bind successor governments (Para 92).

While the Supreme Court of India readily accepted the assurance, the Supreme Court of the UK did not do so. In Miller 1, the Government of UK assured the Court that it would enact a legislation repealing EU law after initiating the process to leave the EU. The Court rejected this submission because the intentions of the government are not law, and that the ‘courts cannot proceed on an assumption that will necessarily become law’ (Para 35). Unfortunately, the Supreme Court of India has proceeded entirely on that assumption.

Concluding remarks

The majority verdict in Miller 1 is not a gold standard. The dissent in that case has been strongly defended on the ground that the majority has unnecessarily curtailed the prerogative powers of the Executive. Nonetheless, the majority opinion does further values of representative democracy, having found those values in an unwritten constitution. In contrast, the plurality in In Re: Article 370, conferred unilateral power upon the executive, even when a written Constitution required direct involvement of the representatives of the people of Jammu & Kashmir.

I would be remiss if I do not point the timeline within which both the courts adjudicated significant constitutional disputes. On June 23, 2016, the UK Government stated its intention to issue a notice to leave the EU. On January 24, 2017, the Supreme Court of UK pronounced its decision in Miller 1. The intervention in R v. Prime Minister (‘Miller 2’) was even more timely. In that case, the question was whether the advice given the Prime Minister to the Queen to prorogue the Parliament was lawful. The advice was given on August 28, 2019 and 11 judges of the UK Supreme Court unanimously ruled on September 24, 2019 that the advice was not lawful. In contrast, the COs in In re: Article 370, were notified in August, 2019 but a decision on their legality was only pronounced in December, 2023. Enough has already been said about the manner in which this case was kept pending. In any case, the Supreme Court seriously needs to introspect on how to avoid delays in cases where it is improbable if not impossible to set the clock back.