SCOTUS decides to not interfere with 26 words that made the internet

Section 230(c)(1) of the Communication Decency Act, 1996 is considered essential for enabling the development of the internet as we know it today. The provision, which consists of 26-words, simply states that a provider of internet services shall not be considered as a publisher of any information provided by a third-party. This enabled intermediaries such as social media websites or search engines to host content posted by users on their platforms, without worrying about being prosecuted for their user’s actions. The Supreme Court of the United States of America (‘SCOTUS’) upheld this provision in Reno v. ACLU. In that case, SCOTUS recognised that the protection offered by these 26 words to providers of internet services, enabled individuals with minimal resources and technical expertise to communicate with others across the globe.

The Judgments in Taamneh and Gonzales

On May 18th, 2023 (26 years after Reno), SCOTUS in Twitter Inc. v. Taamneh and Gonzales v. Google ruled for the intermediaries and chose not to reduce the scope of the 26 words in Section 230(c)(1). In both, Taamneh and Gonzales, Plaintiffs were US citizens whose family members were killed in attacks by ISIS in Paris and Istanbul in 2015 and 2017, respectively. In both the cases, the Plaintiffs sought to impose secondary-liability on intermediaries such as Facebook, Google and Twitter, for the direct actions of ISIS. Their claims were based on Section 2333(d)(2) of the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act, 2016 (‘JASTA’) which imposes secondary liability on anyone who “aids and abets, by knowingly providing substantial assistance” to a person who has committed an act of international terrorism.

The Plaintiffs alleged that the intermediaries aided and abetted ISIS by: (1) providing ISIS social media platforms on which it could load content and communicate with third parties; (2) recommending ISIS content to users most likely to be interested in such content; and (3) not taking sufficient steps in taking down content uploaded by ISIS. Further, specifically with respect to Google, the Plaintiffs also alleged that Google approved ISIS videos on YouTube and thus, shared advertising revenue with ISIS. Each of these actions aided and abetted acts of international terrorism. The Plaintiffs further argued that such conduct of the intermediaries was not protected by Section 230(1)(c) because the intermediaries were not merely providing a space to content published by ISIS but were also recommending ISIS’s content to users. As such, intermediaries were publishers aiding and abetting acts of international terrorism. (See Electronic Frontier Foundation’s response to this argument)

SCOTUS (specifically in Gonzales) entirely sidesteps the Section 230(1)(c) argument (rightly so) by holding that the intermediaries did not aid and abet ISIS. The discussion on intermediaries have not aided and abetted ISIS is in Taamneh, and SCOTUS in Gonzales simply adopts the ruling in Taamneh where Justice Thomas wrote for the Court.

In his opinion, Justice Thomas noted that common-law (since JASTA did not provide much guidance), with respect to aiding and abetting, required that – (1) wrongful act must be performed by the person who defendant aided; (2) defendant must have been generally aware of his role in the overall illegal activity; and (3) defendant must have knowingly and substantially assisted the wrongful act. The rationale is that the law must only hold those liable who are directly, actively and substantially involved in commission of a crime. If we do not apply this standard, bystanders would be punished for actions of others. In Justice Thomas’s words, “ordinary merchants could become liable for any misuse of their goods and services, no matter how attenuated their relationship with the wrongdoer”.

After culling out this standard, Justice Thomas ruled that while the conduct of the intermediaries satisfy the first two elements, the Plaintiffs could not prove that the intermediaries knowingly and substantially assisted in commissioning the attacks in Paris and Turkey. For particular relevance here was the fact that the intermediaries did not treat ISIS any differently from the billions of people that use their platform. Their relations (and even support) was at arm’s length, passive and indifferent. And with respect to the attacks in question, it is even more remote as intermediaries could not have been aware of them.

Relevance for India

Most countries across the world now protect intermediaries from liability which may arise because of conduct of third-parties. These provisions, which are similarly worded to Section 230(c)(1), provide what is known as safe-harbour. In India, Section 79(1) of the Information Technology Act, 2000 is the safe-harbour provision which unlike Section 230(c)(1), expressly states that intermediaries shall not be liable for any third-party information, data, or communication made available or hosted by him. However, Section 79(3)(a) states that this protection shall not granted if the intermediary has “conspired or abetted or aided or induced” the commissioning of an unlawful act. The decision in Taamneh provides much needed guidance to understanding what constitutes aiding or abetting.

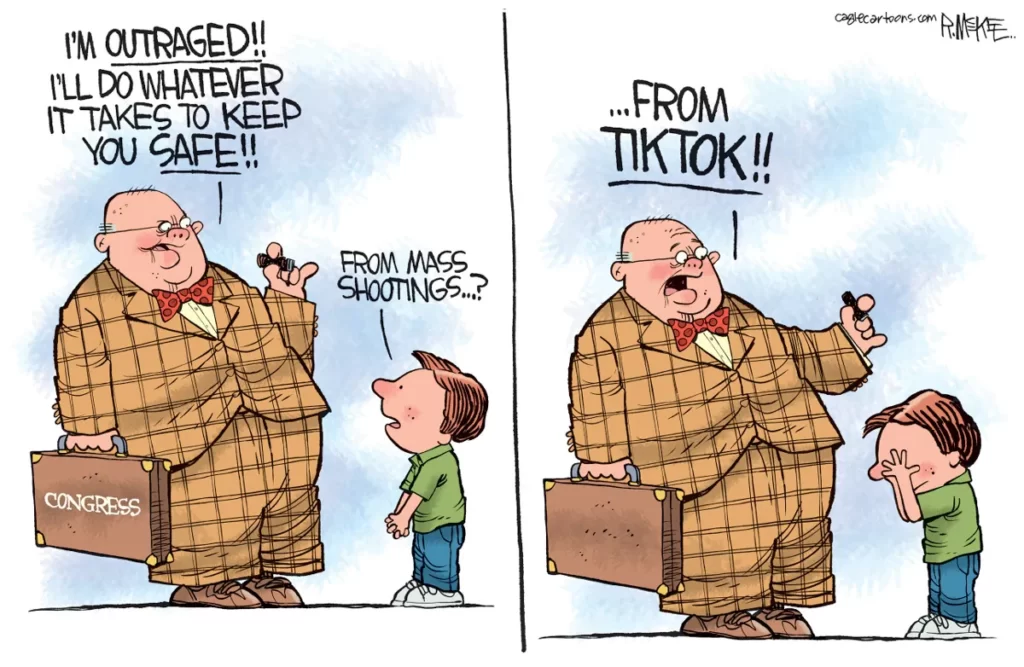

Lastly, beyond the question of aiding and abetting, it is important to flag that while SCOTUS chose not to provide a narrow interpretation to Section 230(1)(c), the US Congress is considering weakening it. In India, the Minister of State for Electronics and Information Technology has also stated that the forthcoming Digital India Act will do away with safe harbour altogether! This could be disastrous. Although regulations are needed to prevent situations such as intermediaries unwittingly helping ISIS or pedophiles, doing away with safe-harbour entirely would seriously hamper innovation. I would not create a platform like Facebook or WhatsApp or Twitter, if I am liable for what others post.

In times like these, it is important to remember what the position was before the Parliament amended Section 79 in 2008. Back then, intermediaries would not be liable for third-party content only if they could prove that the offence was committed without their knowledge. Note how the onus was on the intermediary unlike the position now which requires the prosecution to prove that the intermediary aided or abetted. Thus, under that law, platforms were prosecuted if drugs were sold on their website or if someone posted an MMS. This certainly hampered growth but also curtailed speech, as platforms would censor anything law enforcement would not like. The Minister of State now wants to go back to that state of affairs.