Law Commission’s report on Sedition: My reservations

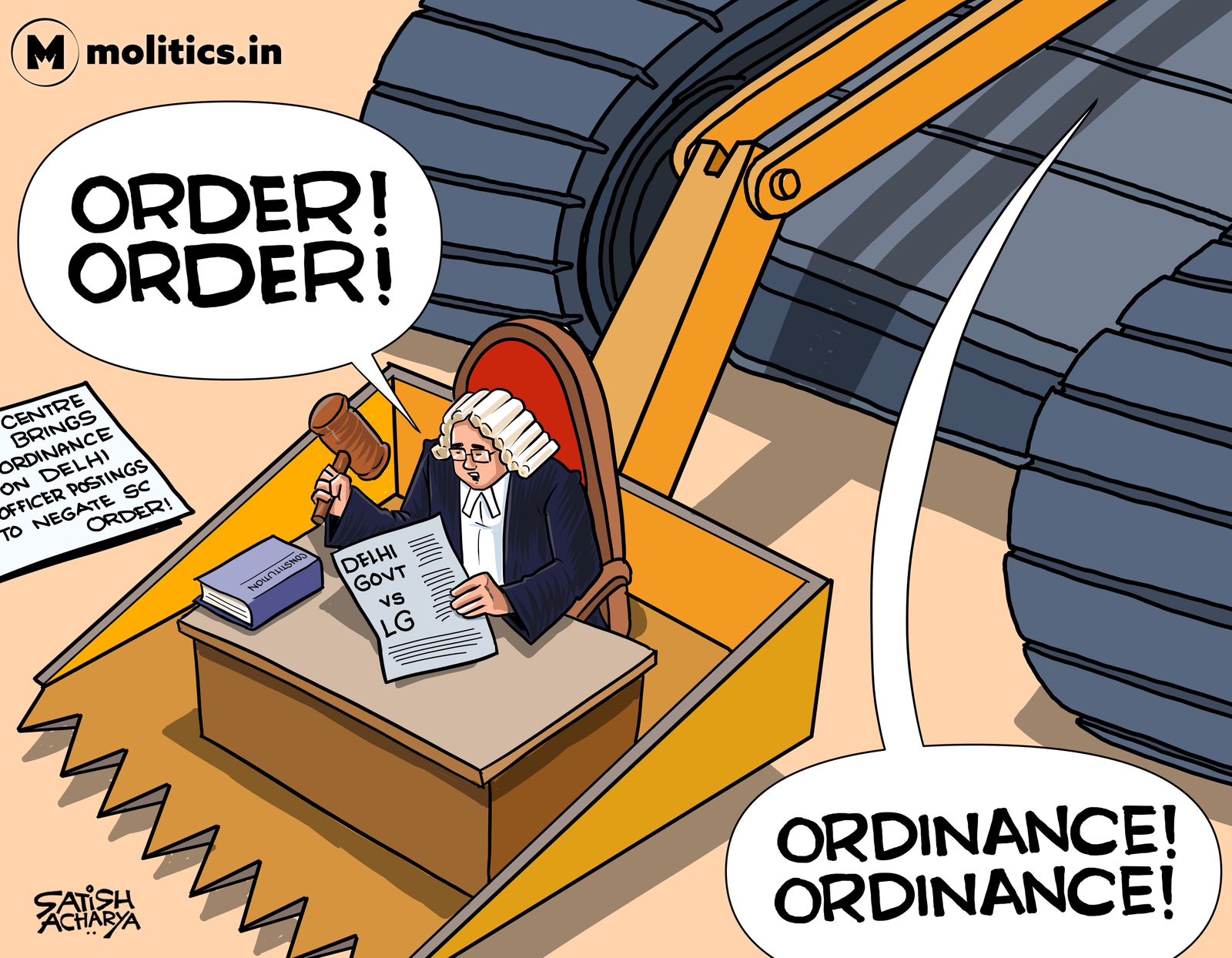

This morning, the Law Commission of India headed by Justice (retd.) Ritu Raj Awasthi, published it’s 279th report on Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. The report has recommended the retention of the provision in the statute books with a meaningless amendment, even as the Supreme Court is adjudicating its validity and last year had directed Central and State governments to not implement it.

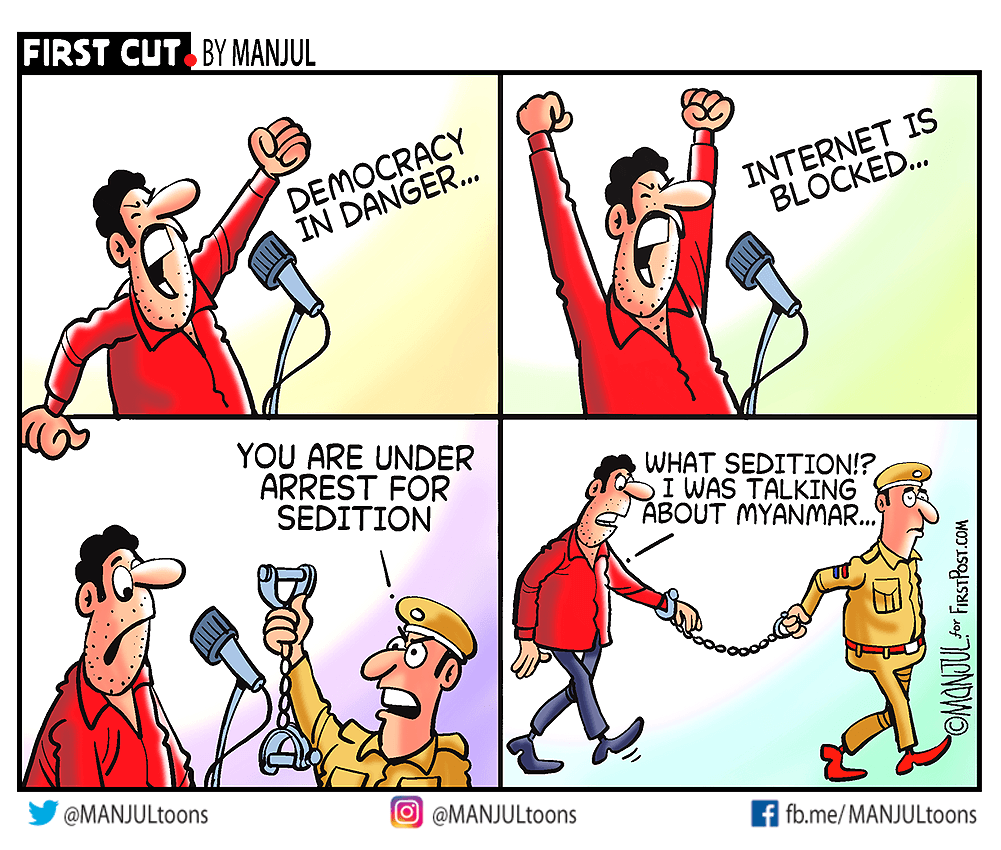

For the uninitiated Section 124A punishes speech that ‘brings or attempts to bring into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards the government established by law’ with imprisonment, which could either be for life or up to three years only, but nothing in between. This palpably broad law which consciously chooses not to define ‘hatred’ or ‘contempt’ and expands the expression ‘disaffection’ to include disloyalty, was introduced by the British in its colonies to suppress any dissent. Until the Supreme Court’s direction from last year, there had been marked increase in the enforcement of this provision since 2014 even though convictions remained abysmally law – demonstrating that the singular purpose of this law is to harass dissidents with legal proceedings.

A Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court in Kedar Nath Singh v. State of Bihar examinded the validity of this provision. The Court was unanimously of the opinion that if read literally, the provision violated the right to freedom of speech and expression. Consequently, the Court effectively rewrote the provision and limited its application to only such speech which has a ‘tendency to incite violence or cause public disorder’. The Law Commission has now recommended that the text of the provision should be amended to incorporate the ruling in Kedar Nath Singh.

The Law Commission’s recommendation and how it has justified it, is misplaced because of the reasons listed below:

- The Law Commission has not engaged with 50 years of jurisprudence on speech since Kedar Nath Singh

The Report consists of 10 parts. It considers previous reports of the Commission, discussions in the Constituent Assembly, judicial interpretation of Section 124A (including Kedar Nath Singh) and it’s ‘alleged’ misuse. Shockingly, the Report turns a blind eye towards how Supreme Court has examined provisions restricting speech since Kedar Nath Singh. In it’s recent jurisprudence the Supreme Court has turned a page from the ‘tendency-test’ provided in Kedar Nath Singh. The Court has consistently required that in order to punish speech, there must be a proximate connected between the speech and the ensuing public disorder or violence (S. Rangarajan v. P. Jagjivan Ram). The speech must be intrinsically dangerous and a mere tendency, which is probabilistic in nature, is not sufficient to constitute a reasonable restriction under Article 19(2) (Shreya Singhal v. Union of India). If the Law Commission had referred to these cases, it would have appreciated that Kedar Nath Singh requires reconsideration.

- The recommended change is constitutionally suspect because of overbreadth

As mentioned above, the Law Commission wants Section 124A to be amended to penalise such speech which being into hatred Government established by law, with a tendency to incite violence or cause public disorder. Here, the Law Commission has recommended the introduction of an explanation to the provision which would define ‘tendency’ to mean ‘mere inclination to incite violence or or cause public disorder rather than proof of actual violence or imminent threat to violence’.

This, as stated above, entirely ignores how Supreme Court has required a proximate connection between speech and violence. But beyond that, such a provision is extremely overbroad. Since Chintaman Rao v. State of MP, the Supreme Court has frowned upon provisions which are so broadly worded that they capture both constitutionally permissible activity and impermissible activity within their scope. The Law Commission’s insistence to continue with undefined broad words such as ‘hatred’ and ‘contempt’ coupled with a definition of tendency which could include any dissent within its ambit, certainly captures entirely constitutionally permissible, and perhaps even constitutionally encouraged, speech.

- Rebuttals to the grounds cited by the Law Commission

After listing the ‘myriad threats to India’s internal security’ in Chapter 6, the Law Commission provides 5 justifications to continue with Section 124A – 1) Safeguard the Unity and Integrity of India; 2) Sedition is a reasonable restriction under Article 19(2); 3) Existence of counter-terror legislations does not obviate the need for Section 124A; 4) Sedition being a colonial legacy is not a valid ground for its repeal; and 5) Realities differ in every jurisdiction.

If you notice closely, only safeguarding unity and integrity of India is a justification to continue with Section 124A. The rest are, in fact, responses to arguments against Section 124A.

In any case, safeguarding unity and integrity of India is a classic case of a strawman, i.e. an imaginary justification. Here, Law Commission provides a seemingly reasonable argument that every society has a right to protect itself against attempts to overthrow government through violent means. While this is a correct proposition, it is still not a justification for Section 124A which does not only penalise speech which seeks violent overthrow the government. As detailed above, the section goes way beyond penalising speech which affects unity and integrity of India. In fact, the gravamen of the offence is public disorder (considering the ruling in Kedar Nath Singh) and even then, the provision does not require incitement of public disorder but only a mere tendency.

The Commission’s responses to arguments against Section 124A do not help it’s case. First, the Commission, like the Supreme Court in Kedar Nath Singh, entirely ignores the import of the expression ‘reasonable restriction’. We have already discussed that reasonableness requires proximity between speech and the ensuing public disorder. But the Commission has not even referred to several Supreme Court cases which arrive at that conclusion. Second, it is nobody’s case that existence of counter-terror legislations obviates the need for Section 124A. Third, while sedition being a colonial legacy is not a ground for its repeal, it is certainly a ground to not presume that the provision is constitutional (See Joseph Shine v. Union of India). Lastly, merely because realities are different in other jurisdictions, does not mean that we should ignore that other countries decided to repeal/strike down identically worded provisions because they violated freedom of speech.

Conclusion

The Law Commission plays an important role in our polity. Its recommendations have a persuasive value on both the Executive and the Judiciary. This report, unlike some of the previous reports I have read, does not make a strong case. Even at its best, its recommendation is merely that Section 124A should be rewritten in accordance with the ruling in Kedar Nath Singh. With all due respect, this is has little value as Kedar Nath Singh’s interpretation has been the position of law since 50 years now.

In any case, it will be interesting to see how the the Supreme Court considers the report as it adjudicates the validity of Section 124A. Interestingally, the Law Minister has already stated that the Report is not binding on the government. It is also interesting that officials from the Union Government did not provide feedback to the Law Commission on the Report, unlike the Report on Adverse Possession, where officials from the Union Government dissented. This suggests that the Union Government might take a different approach from the Law Commission but one should not be too hopeful.

[Disclaimer: I have represented for one of the parties challenging Section 124A before the Supreme Court and I was involved in drafting the petition for them]

Wow

very nicely written