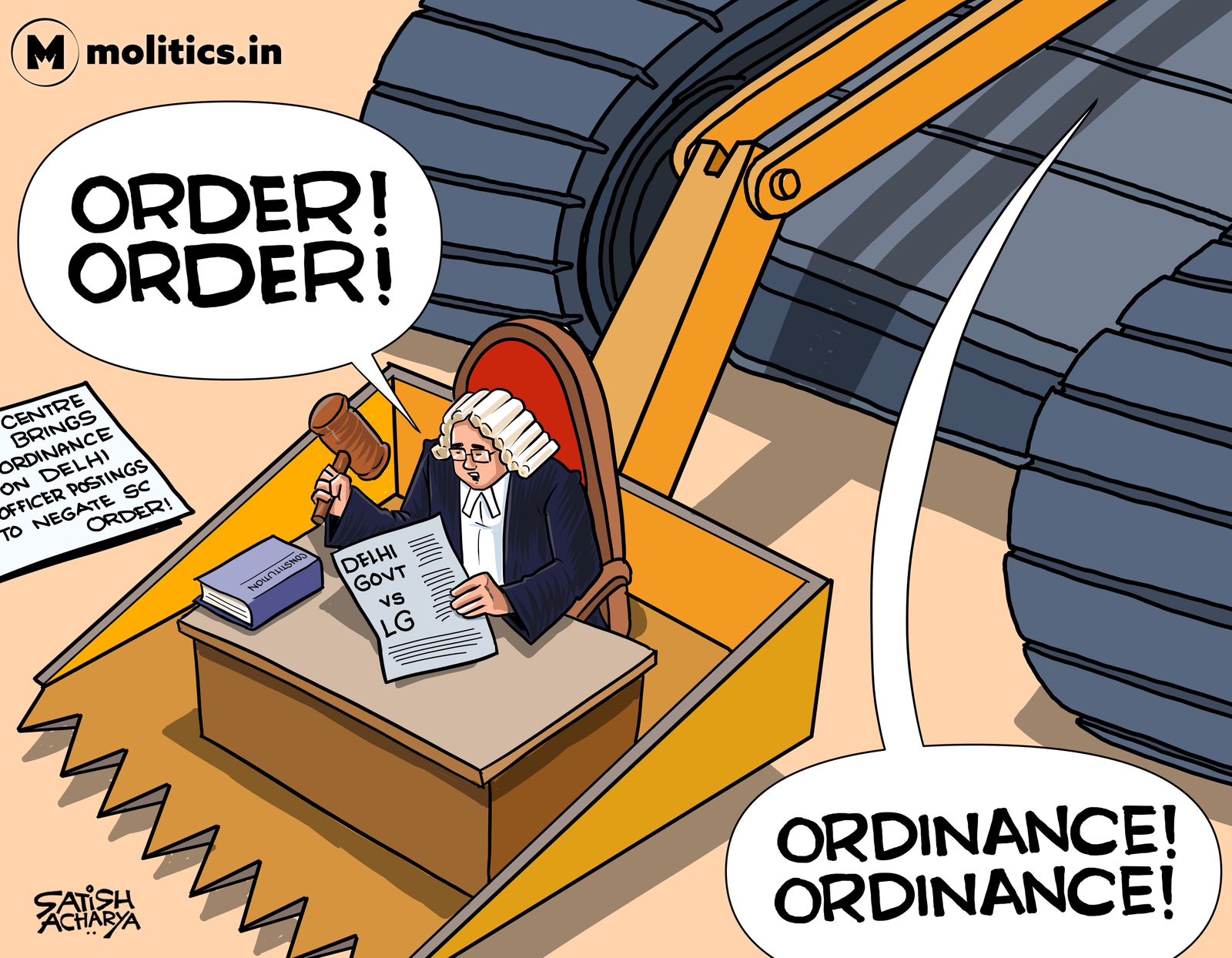

On the Unlimited Power of Review in Writ Proceedings

[This post was originally published on Indian Constitution Law and Philosophy (here)]In this belated post, I discuss the judgment of the Supreme Court passed in Kantaru Rajeevaru vs Indian Young Lawyers Association on 11th of May 2020 (For the sake of convenience, hereinafter referred to as 11th May order). In this order, a 9 Judge bench of the Supreme Court has detailed the reasons for holding that questions of law can be referred to a larger bench in a review petition. I specifically focus on the part of the order wherein the bench has held that there are no limitations on the Supreme Court in reviewing judgments in writ proceedings. The consequence of this ruling is that review petitioners in writ proceedings do not have to meet the high threshold of Order XLVII Rule 1 of the Code of Civil Procedure (“Code”). Order XLVII Rule 1 of the Code permits review of judgments only if there is discovery of new evidence or an error apparent on the face of the record or any other sufficient reason which is analogous to the first two. Indeed, parties have begun to rely on this order already. It is noteworthy to look at the brief written submissions of the review petitioners in Shantha Sinha and Another vs Union of India and Another. The review petitioners are seeking a review of Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India, (2019) 1 SCC 1. In their brief written submission they have pointed out that the Court is not hindered by Order XLVII Rule 1 of the Code. In Paragraph 7 they state:

A 9-Judge Constitution Bench of this Court in its Judgment dated 11.05.2020 in the case of Kantaru Rajeevaru v. Indian Young Lawyers Association and Ors, Review Petition (C) No. 3358/2018 in WP (C) No. 373/2006, while considering the maintainability of the reference, has held that in review petitions arising out of writ petition, this Court under Article 137 read with Article 141 and 142, has wide powers to correct the position of law. It further held that this Court is not hindered by the limitation of Order XLVII Rule 1 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, since writ petition are not ‘civil proceedings’ as specified in Order XLVII Rule 1 of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013

In view of this, it is necessary to analyze the order.

BACKGROUND

Before I begin a critique of the 11th May order, a recap of the ‘Sabarimala Dispute’ and a background of how the 9-Judge bench came to arrive at the aforementioned conclusion is necessary. Indian Young Lawyers Association had filed a Writ Petition challenging the validity of Rule 3(b) of the Kerala Hindu Places of Worship (Authorization of Entry) Rules, 1965 and sought directions to State of Kerala to permit female devotees between the ages of 10 to 50 years to enter Sabarimala temple without any restriction. The case was titled Indian Young Lawyers Association vs State of Kerela (“Indian Young Lawyers Association”). On 28th September 2018, by a majority of 4:1 the Supreme Court allowed the Writ Petition and held inter alia that Rule 3(b) was violative of Article 25(1) of the Constitution of India ( Accordingly, women between the ages of 10 to 50 years were permitted to enter the Sabrimala temple.

A number of review petitions and writ petitions were filed against this Judgment. On 14th November 2019, a Judgment in these review petitions was pronounced and was titled Kantaru Rajeevaru vs Indian Young Lawyers Association (“Kantaru Rajeevaru”). In Kantaru Rajeevaru the Judgment in Indian Young Lawyers Association was not stayed. However, a majority of three judges was of the view that the Court should ‘evolve a judicial policy’ and a larger bench of not less than seven judges should put at rest the conflict between Freedom of Religion and other Fundamental Rights guaranteed in Part III. Hence, the majority referred seven issues to a larger bench and stated that the review petitions and the writ petitions were to remain pending while the larger bench decides the reference. Nariman J and Chadrachud J dissented and held that neither were grounds for review made out nor was a reference to a larger bench called for (Kantaru Rajeevaru has been previously critiqued on this blog).

A bench of nine judges was thereafter constituted to answer the reference. When the hearing before the nine judge bench began, a number of parties raised an objection to the reference. They contended that the review petitions in Kantara Rajeevaru were not maintainable because of the limitations in Order XLVII of Supreme Court Rules and hence, the reference arising out of those review petitions was bad. In the alternative, they submitted that reference to a larger bench is permissible only after review is granted. They also contended that hypothetical questions of law should not be referred. On 10th February 2020, the 9 Judge bench dismissed these contentions and through the 11th May order the bench has provided their reasons. The reasoning of the bench in the 11th May order proceeds in the following manner. The bench firstly referred to Order XLVII Rule 1 of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013 (Paragraph 11), which states:

“The Court may review its judgment or order, but no application for review will be entertained in a civil proceeding except on the ground mentioned in Order XLVII, rule I of the Code, and in a criminal proceeding except on the ground of an error apparent on the face of the record.”

By a literal interpretation of this rule, the bench held that the power to review judgments is plenary and limitations exist only in the context of civil proceedings and criminal proceedings (Paragraph 12). Writ Petitions filed under Article 32 of the Constitution do not fall within the purview of civil and criminal proceedings (Paragraph 14). The review petitions in Kantaru Rajeevaru had arisen from a Writ Petition under Article 32. (Paragraph 18). The bench then dismissed the alternative submission of the parties that reference can only be made after grant of review citing Order VI Rule 2 of Supreme Court Rules, 2013 and Article 142 of the Constitution (Paragraph 19 to 25). The bench then proceeded to hold that pure questions of law could be referred to and answered by a larger bench (Paragraph 25 to 29). Then in Paragraph 30 the bench concluded that the review petitions and the references arising from the review petitions were maintainable.

CONCERNS

In this post, I am primarily concerned with the observation made in Paragraphs 11 to 18 and the conclusion drawn in Paragraph 30 that the review petitions are maintainable. There are three concerns I have with the 11th May Judgment which have been detailed below.

Firstly, there is the question of judicial propriety. In Kantaru Rajeevaru, a majority of three judges had referred questions of law to a larger bench while keeping the review petitions pending. They had not commented on the maintainability of the review petitions nor had they referred the question of maintainability to the larger bench. Therefore, strictly speaking, the nine judge bench by holding that the review petitions are maintainable, seems to have traversed beyond its brief and decided an issue pending before the 5 judge bench. The consequence of this ruling is that once the 9 judge bench does evolve a ‘judicial policy’ and the ‘Sabarimala dispute’ is sent back to the 5 Judge bench, that bench will not be able to decide on the maintainability of the review petitions. It is crucial to note that 2 judges of the bench in Kantaru Rajeevaru (Nariman J and Chandrachud J) had held that the grounds for review were not made out. More crucially, the majority had not commented on the maintainability of the review petitions.

Secondly, the manner in which the review petitions were held to be maintainable is also concerning. The bench has perhaps justifiably held that there are no express limitations on the power to review except in the context of civil and criminal proceedings. However, that ipso facto does not mean that review petition in Kantaru Rejeevaru should be admitted. In a catena of judgments over the years, the Supreme Court has repeatedly insisted that the power to review must be exercised sparingly. In Northern India Caterers (India) Ltd. v. Lt. Governor of Delhi, (1980) 2 SCC 167, for himself and Tulzapurkar, J. observed:

“……Power to review its judgments has been conferred on the Supreme Court by Article 137 of the Constitution, and that power is subject to the provisions of any law made by Parliament or the rules made under Article 145. In a civil proceeding, an application for review is entertained only on a ground mentioned in Order 47 Rule 1 of the Code of Civil Procedure, and in a criminal proceeding on the ground of an error apparent on the face of the record (Order 40 Rule 1, Supreme Court Rules, 1966). But whatever the nature of the proceeding, it is beyond dispute that a review proceeding cannot be equated with the original hearing of the case, and the finality of the judgment delivered by the Court will not be reconsidered except “where a glaring omission or patent mistake or like grave error has crept in earlier by judicial fallibility”: Sow Chandra Kantev. Sheikh Habib [(1975) 1 SCC 674 : 1975 SCC (Tax) 200 : (1975) 3 SCR 933].”

The 9 Judge bench throughout its 29 Page decision has not pointed out the ‘patent mistake’ or a ‘grave error’ that has been committed by the majority of 4 judges in Indian Young Lawyers Association that their judgment must be reviewed. On the other hand Nariman J in Kantaru Rajeevaru had painstakingly analysed all the judgments in Indian Young Lawyers Association, applied the standards of review and held that the grounds for review were not made out.

This leads me to my third concern. The 9 judge bench decision does not provide for any standards which the Court ought to apply while deciding whether to review a judgment arising out of writ proceedings. In the past the Court has applied standards similar to Order XLVII Rule 1 of the Code. For instance, in Sarla Mudgal vs Union of India (1995) 3 SCC 635, 4 Writ Petitions were filed questioning whether a husband, married under Hindu law, can solemnise a second marriage by embracing Islam and without dissolving the first marriage under law. The Court held that in such cases a second marriage would be invalid. In Lily Thomas vs Union of India (2000) 6 SCC 224, petitions were filed seeking review of the decision in Sarla Mudgal. R.P Sethi J, in his concurring judgment, put the contentions of the review petitioners to the standards Order XLVII Rule 1 of the Code and held:

“Otherwise also no ground as envisaged under Order XL of the Supreme Court Rules read with Order 47 of the Code of Civil Procedure has been pleaded in the review petition or canvassed before us during the arguments for the purposes of reviewing the judgment in Sarla Mudgal case [Sarla Mudgal, President, Kalyani v. Union of India, (1995) 3 SCC 635 : 1995 SCC (Cri) 569]. It is not the case of the petitioners that they have discovered any new and important matter which after the exercise of due diligence was not within their knowledge or could not be brought to the notice of the Court at the time of passing of the judgment. All pleas raised before us were in fact addressed for and on behalf of the petitioners before the Bench which, after considering those pleas, passed the judgment in Sarla Mudgal case [Sarla Mudgal, President, Kalyani v. Union of India, (1995) 3 SCC 635 : 1995 SCC (Cri) 569] . We have also not found any mistake or error apparent on the face of the record requiring a review. Error contemplated under the rule must be such which is apparent on the face of the record and not an error which has to be fished out and searched. It must be an error of inadvertence. No such error has been pointed out by the learned counsel appearing for the parties seeking review of the judgment. The only arguments advanced were that the judgment interpreting Section 494 amounted to violation of some of the fundamental rights. No other sufficient cause has been shown for reviewing the judgment. The words “any other sufficient reason appearing in Order 47 Rule 1 CPC” must mean “a reason sufficient on grounds at least analogous to those specified in the rule” as was held in Chhajju Ram v. Neki [AIR 1922 PC 112 : 49 IA 144] and approved by this Court in Moran Mar Basselios Catholicos v. Most Rev. Mar Poulose Athanasius [AIR 1954 SC 526 : (1955) 1 SCR 520] . Error apparent on the face of the proceedings is an error which is based on clear ignorance or disregard of the provisions of law. In T.C. Basappa v. T. Nagappa [AIR 1954 SC 440 : (1955) 1 SCR 250] this Court held that such error is an error which is a patent error and not a mere wrong decision…….

Therefore, it can safely be held that the petitioners have not made out any case within the meaning of Article 137 read with Order XL of the Supreme Court Rules and Order 47 Rule 1 CPC for reviewing the judgment in Sarla Mudgal case [Sarla Mudgal, President, Kalyani v. Union of India, (1995) 3 SCC 635 : 1995 SCC (Cri) 569] . The petition is misconceived and bereft of any substance.”

Indeed, as mentioned above, Nariman J in Kantaru Rajeevaru also put the contentions of the review petitioners through similar standards. The 9 Judge bench, however, by not undertaking such an exercise, has raised questions of what exercise ought to be undertaken. The judgment on a number of occasions has stated that Order XLVII Rule 1 of the Code is inapplicable to judgments arising out of writ proceedings. If that is the case, there needs to be clarity on the applicable standard. The need of having a standard cannot be understated. Order XLVII Rule 1 of the Code has ensured that there is a finality to judgments delivered by Court and at the same time has provided a mechanism to ensure that injustice is not committed. In absence of this Rule, any party dissatisfied with the decision of the Court will seek a re-hearing and the litigation will be endless.

CONCLUSION

To sum up, three concerns with the 11th May Judgments have been pointed out above. The first pertains to which bench was the most suited to address the question of maintainability. The second concern points out the lackadaisical manner in which the 11th May Judgment holds the Kantaru Rajeevaru review petitions to be maintainable. And lastly, the third concern raises a question for the future as there needs be clarity on the manner in which the Apex Court is going to entertain review petitions.