A Tale of a Commission and a Committee

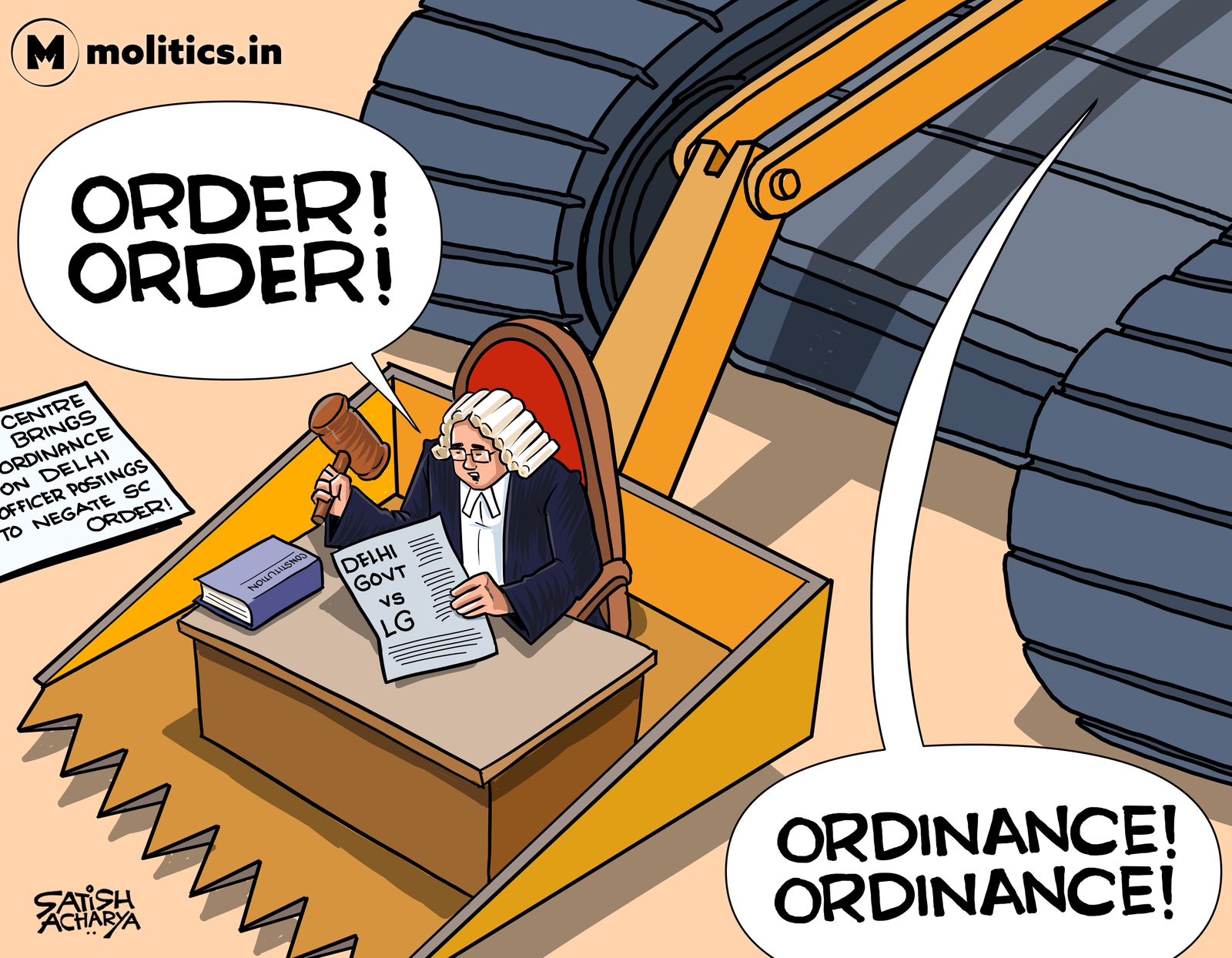

[This post was originally published on Indian Constitution Law and Philosophy (here)]On December 16, 2021, the counsel for an NGO named Global Village Foundation Public Charitable Trust mentioned before the Chief Justice of India a petition challenging the constitution of the Commission of Inquiry (‘Commission’) by the State of West Bengal under the Commission of Inquiry Act, 1952 (‘Act’). The Commission was constituted to inter alia enquire into whether the Pegasus Spyware was used to surveil individuals in West Bengal, and the role of State/Non-State actors in such surveillance. Based on this mentioning, the petition was listed the very next day, and the Court by order dated December 17, 2021 (‘17.12.21 Order’) stayed the proceedings of the Commission (which is headed by a former judge of the Supreme Court.) Incidentally, December 17, 2021, was also the last working day of the Court before winter vacations.

The 17.12.21 Order is as intriguing as it is minimalist. It records that on August 25, 2021, the counsel for the petitioner had sought a stay on the proceedings of the Commission to which the counsel for West Bengal (not the Commission) had stated that ‘no orders would be necessary’. Yet the Commission continued with the proceedings, and that the counsel for West Bengal submitted that they could not make a statement on behalf of the Commission (even though they did so on August 25, 2021). The Court held that the Commission should be impleaded as a party but also held that the proceedings of the Commission should remain stayed in the meanwhile.

The 17.12.21 Order raises several questions as it is not immediately clear why the Court stayed the proceedings. Media reports suggests that the Court stayed the Commissions proceedings because it has formed a committee of its own to investigate the use of Pegasus, and it did not want ‘parallel inquiries’. But the Court chooses not to record this in the 17.12.21 Order. Instead, it has prohibited the Commission from continuing with its proceedings without recording reasons, without hearing the counsel for the Commission, and at the behest of an NGO which does not seem to have any relationship with the case, its subject matter, or even the State of West Bengal.

To appreciate these concerns, a background of the Commission is necessary. The Commission was appointed by the State of West Bengal on July 26th, 2021 in the wake of disclosures by an international consortium of journalists that 300 Indian mobile telephone numbers were surveilled using spyware called ‘Pegasus’. These phone numbers included those used by ministers, opposition leaders, journalists and the family of the complainant who accused a former Chief Justice of India of sexual harassment. The consortium also reported that the Pegasus Spyware could be installed on a phone without any action on part of the victim, and once installed it can collect and transmit data, track activities such as browsing history, and control functionalities such as the phone camera. Notably, Pegasus is manufactured by an Israeli cyber-arms firm called the NSO Group, and according to the NSO Group itself, sold only to ‘vetted government(s)’.

While the State of West Bengal appointed the Commission to examine whether Pegasus was used in West Bengal, the Central Government dismissed the disclosures. Left remediless, several individuals, including those whose phones were forensically analysed, approached the Supreme Court seeking relief against the violation of their fundamental rights. The Court conducted its first hearing on August 5, 2021, and on October 27, 2021, formed a Technical Committee (‘Committee’) to inter alia examine whether the Pegasus Spyware was used on phones or other devices of the citizens of India. While the Committee has been directed to submit its report ‘expeditiously’, the Commission had to submit its report to the State Government within six (6) months from July 26, 2021, i.e. by January 26, 2022. Moreover, while the Committee has only recently issued a public notice inviting any citizen who may have felt that their phone was infected by Pegasus malware, the Commission issued a public notice as well as notices to several individuals, and has already conducted many hearings. Yet the Court chose to stay the proceedings of the Commission.

The stay raises the following concerns, detailed below –

Firstly, similar to the Supreme Court’s order staying the farm laws (discusssed here on this blog), the 17.12.21 Order does not provide any reason for staying the proceedings of the Commission. The Court could have imposed a stay only if it found the notification constituting the Commission to be ex-facie unconstitutional or that the balance of convenience entirely lied in favour of the petitioners or that it was unjust/unfair for the proceedings of the Commission to continue. We do not know what compelled the Court to issue the 17.12.21 Order, and therein lies the problem. As pointed out previously on this blog, the effect of a minimalist order is that there is nothing one can engage with, disagree with, or critique, and this is deeply irregular because the authority of the Court is founded entirely on reason.

Secondly, assuming that the Court stayed the proceedings because it did not want a ‘parallel inquiry’, it is not clear why that should be the case. There is no legal bar on two bodies inquiring into allegations related to an overlapping set of facts (State of Karnata vs Union of India). Even criminal proceedings and department proceedings can proceed simultaneously (Captain M Paul Anothony vs Bharat Gold Mines Limited & Ors). Unlike both of those proceedings, neither the proceedings before the Commission nor those before the Committee have any teeth at least with respect to the report these bodies may submit. The Commission of Inquiry Act, 1952 does not impose any obligation on the government to act on the recommendations of the Commission, and the Supreme Court itself has held that the role of Commission of Inquiry is to merely enable the government to decide what administrative or legislative measures must be taken to eradicate the evil found (T.T Antony vs. the State of Kerala). Moreover, the Supreme Court has also held that the findings of the Commission of Inquiry are not binding on the Supreme Court (In Sham Kant vs. the State of Maharashtra). Similarly, and surely the report of the Committee is also not binding upon the Supreme Court. As an aside, the Committee’s report may not even be open to public scrutiny if past precedent is anything to go by.

Lastly, the Supreme Court should not have granted interim relief to the NGO without addressing whether the NGO had the locus standi (Soumitra Kumar Sen vs Shyamlal Kumar Sen). On the face of it, the NGO does not seem to have any connection with the disclosures made by the Pegasus Project. The NGO also was not summoned as a deponent by the Commission, and to the best of the knowledge of the author, it did not stand to gain/lose by the continuation of the proceedings. Thus, propriety required that the Court at the least detailed why the submissions of the NGO were accepted, especially since the State of West Bengal had questioned their bona fides.

As a result of the order of the Court, the Court-Appointed Committee is the only body examining the allegations raised by the petitioners who have reportedly been surveilled by the Pegasus Spyware. The report will be placed before the Court which will then examine the petitions. It is anybody’s guess when this will happen. If the Court had not stayed the proceedings of the Commission, it would have had the benefit of the finding of an enquiry conducted by a former Supreme Court justice. The public at large would have also gotten more details regarding the devious surveillance. But now the Commission has to wait until the next date of hearing (04.02.2022 – computer generated!) before it can seek a vacation of the stay order. Meanwhile, the victims of the Pegasus Spyware keep waiting for relief in the hope that their phones are not being surveilled.

Disclaimer: The author was one of the lawyers representing the petitioners who approached the Supreme Court seeking relief against the use of Pegasus Spyware on them.