Data Protection – DPDPA casts a wide net #2

Every legislation contains a provision demarcating the scope of its application. Data Protection legislations contain provisions which delineate their Territorial Scope and Material Scope. Sections 3(a) and (b) of the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (DPDPA) defines its Territorial Scope, while Section 3(c) outlines its Material Scope. In this second post in the series on DPDPA, I examine the Sections 3(a) and (b) and discuss how they are materially different from a comparative provision in Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This is an important exercise because data protection legislations, including DPDPA, govern activities which are agnostic to physical boundaries. Thus, these legislations, unlike other legislations, often regulate activities which happen outside of national boundaries to protect individuals within those boundaries. Hence, understanding the Territorial Scope of DPDPA is necessary for any entity anywhere in the world which intends to collect, use or share personal data of anyone in India.

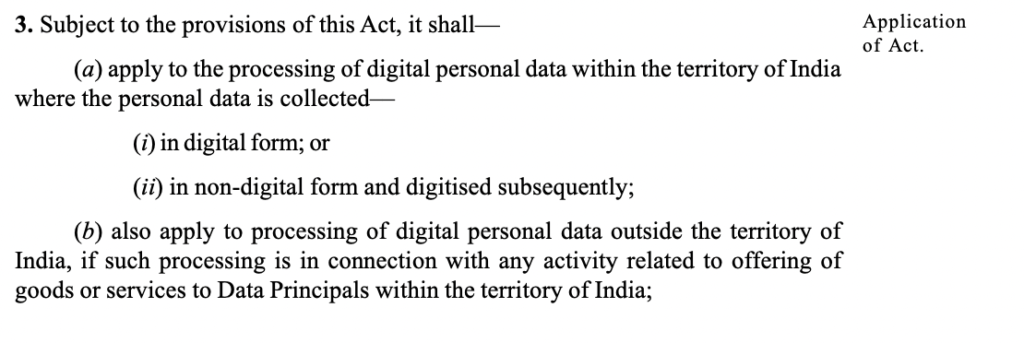

The Territorially Dependent Section 3(a)

As mentioned above, Sections 3(a) and (b) delineate the scope of DPDPA in a spatial sense. They outline what activity, within or outside India will activate the application of the statute. Here, Section 3(a) is territory dependent and Section 3(b) is territory independent.

Section 3(a) is concerned with what is happening in India. Importantly, Section 3(a) does not restrict itself to personal data of Indian citizens. In fact, it does not even restrict itself to personal data of those who are in India. Thus, any processing by any entity in India would fall under the scope of the DPDPA, regardless of the location or the nationality of the data principal whose personal data is being processed. Thus, even a ride-hailing service based in India which caters only to residents of the United Kingdom, would have to comply with the rigours of DPDPA if it processes the data of the residents in India.

Article 3(1) of GDPR is comparable to Section 3(a). However, unlike Section 3(a), which requires processing of personal data to take place in India, Article 3(1) applies even if the processing takes place out European Union as long as the Data Fiduciary is from the Union. This difference is crucial as it highlights that companies established in India can avoid compliance with DPDPA if – a) they process personal data outside India; and b) they process data of individuals who are not in India.

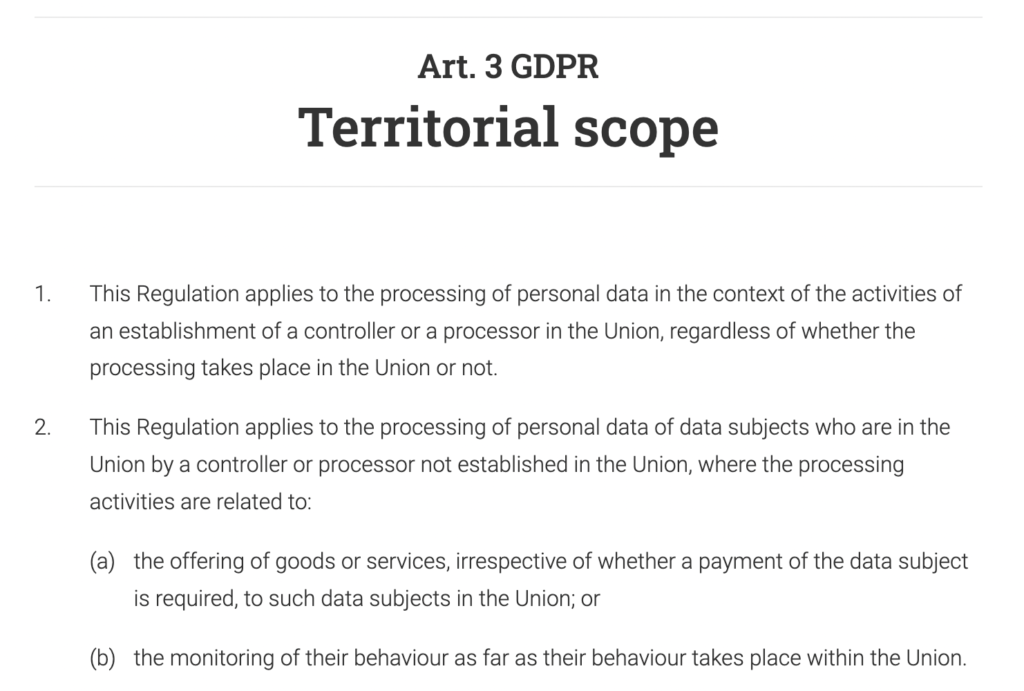

The Territorially Independent Section 3(b)

Section 3(b) is more interesting. It brings within the net of DPDPA the activities of any entity (think Facebook or Uber) which is providing goods or services to data principals in India. This provision applies when – a) processing is of personal data of data principals who are in India; and b) if the processing relates to offering of goods or services. The purpose of this provision is to provide parity between entities processing data in India and those outside India, but doing business in India.

This provision is interesting because it creates cross-border obligations. It imposes obligations on entities which are in other jurisdictions. It is comparable to Article 3(2) of the GDPR (see above) which applies to ‘controller or processor not established in the Union’ but offers goods and services to data principals in the Union. The Court of Justice of the European Union examined the scope of this Article in Google Spain SL and Google Inc. v Agencia Española de Protección de Datos (AEPD) and Mario Costeja González. In that case, Google Inc., which operates the search engine, argued that provisions of GDPR did not apply to it as it is based in USA. CJEU rejected this contention as Google Inc. processed data while providing service in Spain and thus, its nationality was irrelevant.

Section 3(b) of the DPDPA would give rise to similar issues in the future considering the large number of foreign entities which provide goods or services in India without have a legal presence. In adjudicating these disputes, it is crucial that the Data Protection Board recognises that Section 3(b) is a domestic law that creates cross-border obligations and should be applied and interpreted in a manner that is mindful of the restrictions of international law and considerations of international comity.

Conclusion

Sections 3(a) and (b) case a wide net indeed. Similar to GDPR in several ways, it is likely that it may get difficult to justify the application of the legislation on an international stage, as has been the case with GPDR. For example, if a British merchant has online presence in India, and can provide its goods here but most of its customers are British. Should it still comply with every provision under DPDPA if it has a received one or two orders from India? Surely, costs outweigh the benefits here. But beyond this, and perhaps more importantly, DPDPA applies so broadly, as we have seen above, that it may not be possible to ensure its actual enforcement in many situations.

In the next post, I will discuss Section 3(c) of DPDPA which outlines its material scope. As we shall see, unlike 3(a) and (b) which case a wide net, Section 3(c) simply decides to not provide any protection to any personal data which is already in the public domain.

Good