Data Protection: The conspicuous omission of victim compensation in DPDPB, 2022

Recent reporting suggests that the Union Cabinet has approved the Draft Personal Data Protection Bill, 2022 (‘DPDPB, 22’) and it is expected to be tabled in the upcoming Monsoon Session. Apparently, the Cabinet has approved the draft which was floated for public consultation in November, in its entirety. If that is the case, the Union Government has again decided to ignore concerns voiced by experts.

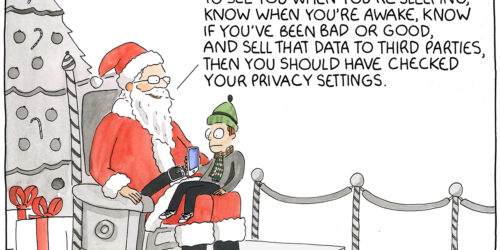

One particular concern with DPDPB, 22 which I want to highlight here is how unlike data protection legislation in other jurisdictions, the proposed bill does not have any provision to compensate data principals (individual to whom the personal data relates) if anyone violates their privacy. I do not overstate when I say that this conscious omission by the Union Government is mind-boggling. The stated purpose of DPDPB, 22 is to protect privacy but if it is violated, the Bill does not even require the violator to cover the victim’s losses.

Let us explore this in detail. In the first part of this post, I examine the scheme of DPDPB, 22 and provide my justification for why I say that this omission is a conscious one. In the second part, I point out that DPDPB, 22 goes a step further from this ommission and not only removes redressal available for data principals under existing law, but also proposes to penalises them if they seek any redressal at all.

Scheme of DPDPB, 22

The preambulatory clause of DPDPB, 22 states that its purpose is to provide for processing of personal data that recognises the right of individuals to protect their personal data. In order to achieve this end, the Bill does two things – 1) imposes obligations on anyone processing personal data – such as taking consent of data principals before processing their data (Clause 7) or undertaking reasonable security safeguards to prevent personal data breach (Clause 9); and 2) recognises the rights of data principals and provides a mechanism to enforce those rights. For example, data principals can demand data fiduciaries (such as Facebook) to provide identities of all data fiduciaries with whom their data has been shared (Clause 13). One of the biggest concerns here is that the Central Government can unilaterally exempt state instrumentalities from the provisions of the Bill. Thus, entities which process a massive amount of sensitive personal data, say National Informatics Centre or law enforcement agencies, may not have the obligation to respect any of your rights. Internet Freedom Foundation has discussed here the surveillance related concerns which arise because of this power to exempt.

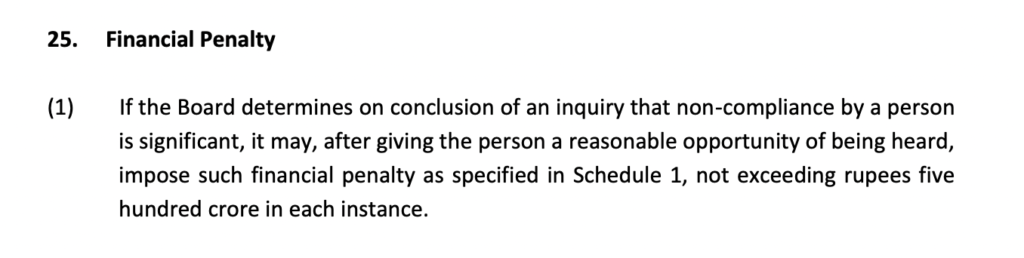

But I digress. To ensure that the non-exempted entities comply with the provisions of the Bill, Clause 19 constitutes a Data Protection Board of India (‘Board’), which will consist of officers appointed by the Central Government. The function of the Board under Clauses 20(1)(a) and 21 is to inquire non-compliance with the provisions of the Bill, on receipt of a complaint by an affected person or on reference made by the Central or State Government. Under Clause 25(1), if the Board determines on conclusion of an inquire that the non-compliance is significant, it may impose a financial penalty on the data fiduciary. Presumably, the penalty will be paid to the Board directly and will be added to the Consolidated Fund of India.

Here, DPDPB, 22 simply does not have a provision to compensate data principals if they have suffered harm because of data fiduciaries non-compliance with the provisions of the Bill. For example, if a data fiduciary does not undertake reasonable security safeguards to prevent breach of X’s personal data (Clause 9) and that data is then used by a third-party to commit identity theft, X cannot even claim compensation from the data fiduciary under DPDPB, 22.

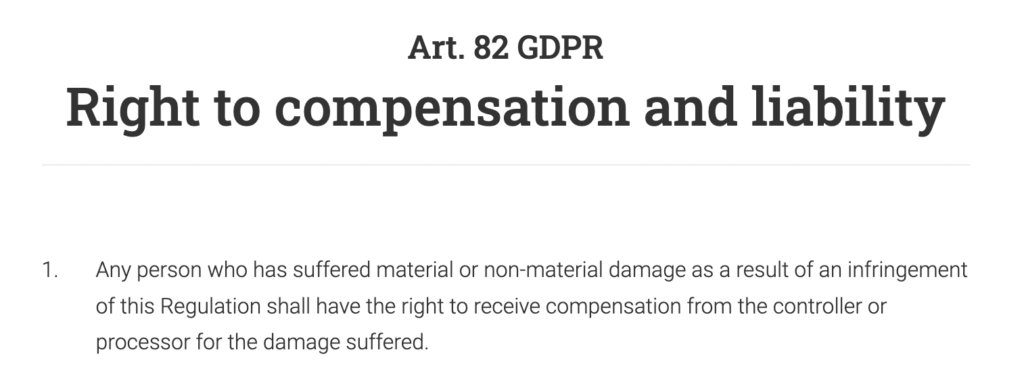

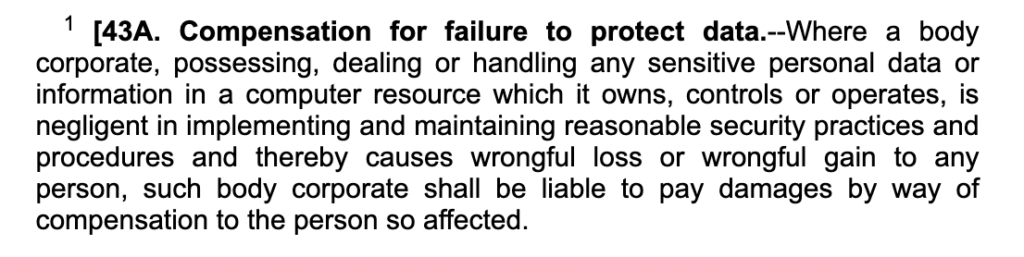

Note that every previous iterations of proposed data protection in India specifically provided data principals the right to seek compensation from data fiduciaries. Clause 65 of the version proposed by the Joint Parliamentary Committee in 2021 specifically provided compensation for data principals if they suffered any harm because of data fiduciaries. Clause 64 of Data Protection Bill, 2019 which was referred to the Joint Parliamentary Committee by Lok Sabha in 2019, contained an identical provision. Further, the Srikrishna Committee Report of 2018 had also proposed that the legislation enable data principals to seek compensation. Similarly, Article 82 of the General Data Protection Regulation, 2016 also entitled data principals to seek compensation for any ‘material or non-material’ harm arising from breach of the Regulation.

Thus, the decision of the Central Government to exclude a victim compensation clause in DPDPB, 22 is certainly a conscious one. It has not yet provided any justification for the same, and one hopes that it provides more clarity on the floor of the House.

Double whammy

If removing the compensation clause is a set-back, several other provisions in DPDPB, 22 make it difficult for data principals to seek any relief. Before we go to those provisions, note that if I am not going to be compensated for a data fiduciary’s non-compliance with the Bill, I do not have much of an incentive to pursue an expensive litigation against that fiduciary. If the omission reduces my incentive of pursuing a litigation, Clause 16(2) eliminates whatever incentive that was remaining. It says that data principal shall not register a ‘false or frivolous’ grievance or complaint with the Board and then empowers the Board to impose a cost of upto Rs. 10,000 if it deems that I have not complied with the mandate of Clause 16(2). This provision is coupled with Clause 21(12) of DPDPB, 22 which in addition empowers the Board issue a warning to the data principal or impose costs, if the Board determines that a complaint is ‘devoid of merit’. Thus, a data principal is not only not going to gain anything personally for pursuing a litigation against a data fiduciary but might even have to pay the Board for fighting for her rights.

If this was not enough, DPDPB, 22 also proposes to omit Section 43A of Information Technology Act, 2000 which is the only statutory provision which entitles data principals to seek compensation against corporates. Again, Central Government has not yet provided any justification for the same.

I wonder whether the purpose of DPDPB, 22 is to protect privacy of data principals or to protect data fiduciaries from the right to privacy of data principals.

1 Response