Data Protection – If its public, its not personal #3

In the last post, I highlighted how the Sections 3(a) and (b) of the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (DPDPA) outlined the Territorial Scope of the legislation. I pointed out that the legislation casts a wide net, much like Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and regulates entities which are not even based in India. However, unlike GDPR, the Material Scope of DPDPA is not wide at all. Section 3(c) which outlines the Material Scope restricts the scope of protection by excluding from DPDPA’s purview – a) any personal data processed by an individual for any personal or domestic purpose (domestic use exemption); and b) any person data that is made publicly available by the data principal or by any other person who is obliged to do so under any law (public information exemption). While there are strong (and rather self-explanatory justifications) for the domestic use exemption, it is unclear why the Government introduced the public information exemption – which is the subject matter of this post.

Before I analyse this exemption, it is important to note that public information exemption was not present in any previous proposed data protection legislations released by public authorities in India for public consultation. For example, Clause 4 of Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2022, restricted the scope of the legislation to only automated processing of data, online personal data, personal data not used for domestic purpose and personal data which has not been in records for over 100 years. The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 did not even have a material scope clause and it sought to bring within its purview even personal data used for domestic purposes. Thus, only on August 3, 2023, the the government informed the public about its decision to provide the public information exemption when it introduced the the Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2023 in Lok Sabha. Since the Bill was then pushed through Lok Sabha within 4 days, there wasn’t any public or legislative debate on this aspect of DPDPA.

The only reason I point this out is that this again demonstrates the surrepticious manner in which consultation process for the DPDPA was conducted. As Derek O’Brien said out in an editorial after the Bill was passed, DPDPA stands out ‘as an example the systematic wreckage of parliamentary procedure.’But why should there have been a debate on the public information exemption? In my opinion, there are several strong justifications for protecting personal information which is in the public domain.

Firstly – and rather, principally – merely because information is in public domain does not mean that it cannot be private and hence, deserve protection. The House of Lords decision in Campbell v. MGN, is instructive. In that case, the Lords held that Daily Mirror’s publication of photographs of a model which disclosed that she was leaving a rehabilitation centre, constituted a misuse of her private information. The Lords arrived at this ruling even though the area outside the rehabilitation centre was a public space, and the fact of her leaving it, was available for public consumption. In a data protection context, the majority of the Supreme Court of the United States of America in United States v. Jones, held that the GPS monitoring of a suspect vehicular movements violated his right to privacy. Sotomayor. J in her concurring opinion even pointed out that it is necessary to reconsider the premise that ‘an individual has no reasonable expectation of privacy in information voluntarily disclosed to third parties.’

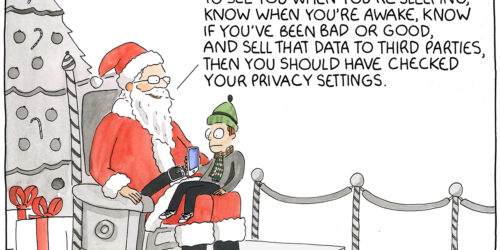

Secondly – as an extension to the first point above – even innocuous personal information in public domain deserves protection in today’s digital economy. Anyone can obtain information from publicly available sources, such as profiles on social media, in order to combine, match or add to information that they already hold on an individual. This can be particularly intrusive, and unexpected, as it can create a very detailed picture of an individual’s affairs. For example, Target figured out that a teenager was pregnant and sent her a catalogue congratulating simply by analysing her buying patterns. Certainly, the purpose of a data protection is to provide individuals with some semblance of control exactly over such information.

This leads me to my third point. Data protection legislations provide individuals control by providing the procedure to access and rectify their personal information available with data fiduciaries. DPDPA says that with respect to public information, individuals will not have either of these rights. So if I make some personal information about me public, such as my sexuality and then later want to find out which data fiduciaries are aware about this, I do not even have the right to access such information. The situation is even more bleak when information about me is made publicly available by someone else under any law. For example, a public authority incorrectly includes me in a list of proclaimed offenders. In other jurisdictions, I would have had a right under data protection legislations to get such information corrected. In India, however, I would not have any remedy at least under DPDPA.

My last concern is that the provision is imprecisely drafted and will inevitably lead to disputes. The provision excludes personal data that ‘made or caused to be made publicly available’ by a data principal or any other person. It is entirely unclear what constitutes ‘publicly available’. Surely, revealing any personal data to a third party, cannot constitute making personal data publicly available. If that is the case, DPDPA will not regulate any processing of personal data. Thus, there is some threshold which must be met. Is that threshold met when I share personal data with my 400 followers on my private instagram or is it necessary that my profile itself should be public? The Data Protection Authority will have to address these problems soon. Unfortunately, as has been argued in this post, this is a problem which we have unnecessarily brought upon ourselves.