Devangana Kalita Bail Order: Protecting the State at the cost of Rule of Law?

Our legal system is not complicated. Inherited from the British, it is based on certain commonsensical principles which ensure parity. The foundational principle in this system is stare decisis, which simply means that a rule established in a previous legal case by Court (say, High Court) is binding on Courts below it (say Sessions Courts) when deciding subsequent cases with similar issues or facts. This principle prevents arbitrary use of judicial power by guaranteeing that similarly placed individuals are treated similarly.

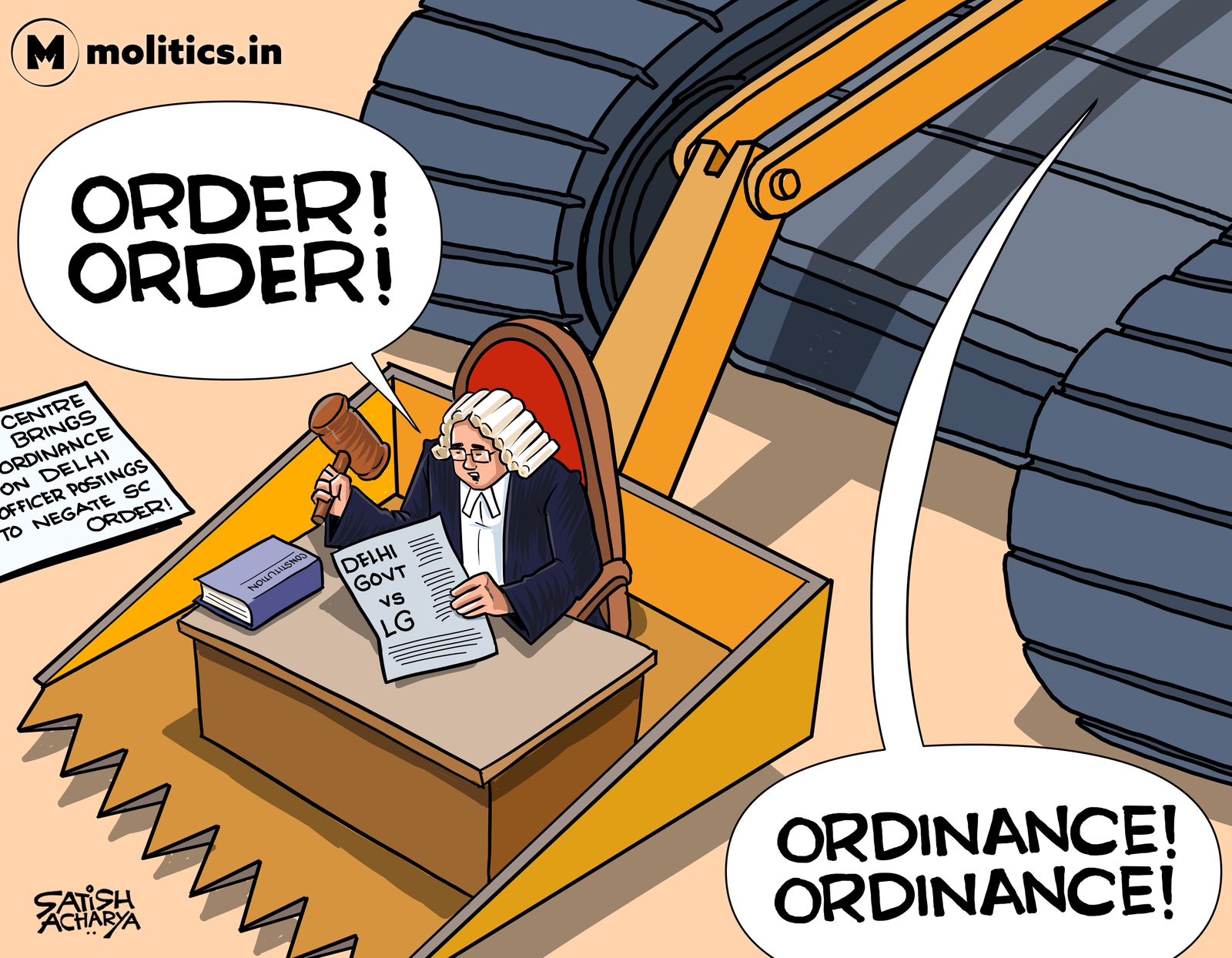

On Tuesday (02.05.2023), the Supreme Court in Devangana Kalita without even providing an explanation and while confirming its previous interim order, directed us to ignore this principle. As a result, three detailed judgments of a division bench of the Delhi High Court (Mridul and Bhambani JJ) granting bail to individuals accused under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, 1967 (‘UAPA’) cannot be treated as a precedence. As argued by Gautam Bhatia, these decisions of the Delhi High Court “provided an ideal template for courts to approach the issue of bail and personal liberty under special statutes such as the UAPA.” The Supreme Court without even commenting on the correctness of these decisions – entirely abdicating its responsibility as the highest appellate court of the country – has directed courts to simply ignore the “ideal template” provided by the Delhi High Court.

I argue that the course adopted by the Supreme Court is simply untenable in law because of two reasons:

- Supreme Court was duty bound to apply its mind: In its interim order in Devangana Kalita dated 18.06.2021, the Supreme Court simply stated that the “impugned judgment shall not be treated as precedent.” In its final decision on Tuesday, a different bench of the Supreme Court retrospectively provided a sentence-long justification for the said direction – stating that the High Court should have only examined whether the accused were entitled to bail or not, without interpreting provisions of UAPA (Gautam Bhatia explains here why this reasoning is fallacious). Beyond this, the Supreme Court has not provided any rationale for why those judgments should not be treated as precedence.

Why is this a matter of concern? First, this does not conform with the standard Supreme Court has set for High Courts. Recently, in State of Orissa & Ors. v. Prasanta Kumar Swain, the Supreme Court was hearing a challenge to the decision of the Orissa High Court which dismissed a challenge to a judgment of the Orissa Administrative Tribunal while stating that it shall not be treated as precedence. The Supreme Court held that “this was an inappropriate manner of disposing a substantive petition under Article 226 of the Constitution since the High Court is duty bound to apply its mind to whether the judgment of the Tribunal is sustainable on facts and law.” The Supreme Court has similarly inappropriately disposed of the special leave petition in Devangana Kalita. Wasn’t it also duty bound to apply its mind on whether the judgment of the High Court was sustainable on facts on the law?

Second, the Supreme Court has consistently held that a decision that does not proceed on consideration of issues cannot be law declared to have a binding effect as is contemplated by Article 141 of the Constitution (See State of UP v. Synthetics & Chemicals Ltd.). In Devangana Kalita, the Supreme Court does not proceed on consideration of issues beyond merely stating that the High Court should have limited itself to the factual scenario. As such, the ruling that decision of the division bench should not have precedential value is highly suspect.

- Lack of legal basis: It is undisputed that Supreme Court can set aside decisions of High Courts. Similarly, the Supreme Court can uphold decisions of High Courts (See, Article 136 of the Constitution of India). The Supreme Court can also remand a case back to the High Court for reconsideration. This is entirely consistent with the powers of appellate courts under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908. The path Supreme Court chose, however, is not a judicially available alternative. Decisions of High Courts are binding by virtue of the fact that they are rulings of a Constitutional court of record (See Krishena Kumar v. Union of India). The Supreme Court cannot deprive rulings of the High Court of this authority, let alone, without even an explanation.

Beyond these concerns, it is important to note the real rationale behind the Supreme Court’s suspect direction, which it itself notes when it says that “the idea (behind not treating Delhi HC’s decisions as precedent) was to protect the State against the use of the judgment on the enunciation of law qua interpretation of the provisions of the UAPA Act in a bail matter.” As Gautam Bhatia correctly points out, this is a world turned upside down – “the Supreme Court is not concerned with protecting individual liberty against the State, but with protecting the State against individuals seeking liberty.”

1 Response