Allahabad HC judicially censors a documentary

The Constitution has assigned courts the role of a sentinel on the qui vive, i.e. they are the watchful guardians of fundamental rights, which includes the right to freedom of speech and expression. On June 14th, 2023 the Allahabad High Court in Sudhir Kumar v. Union of India & Ors., turned this phrase on its head by prohibiting Al Jazeera from releasing its documentary, ‘India..who lit the fuse?’. This documentary is a part of Al Jazeera’s Point Blank investigation series and it examines the activities of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh in India. As a result of the order, the documentary will not be released in India at least until the next date of hearing in Sudhir Kumar.

In this post, I ask 2 questions of the June 14th order: 1) Whether courts can judicially censor speech?; and if yes, 2) How should courts exercise the power to censor speech?

Whether courts can censor speech?

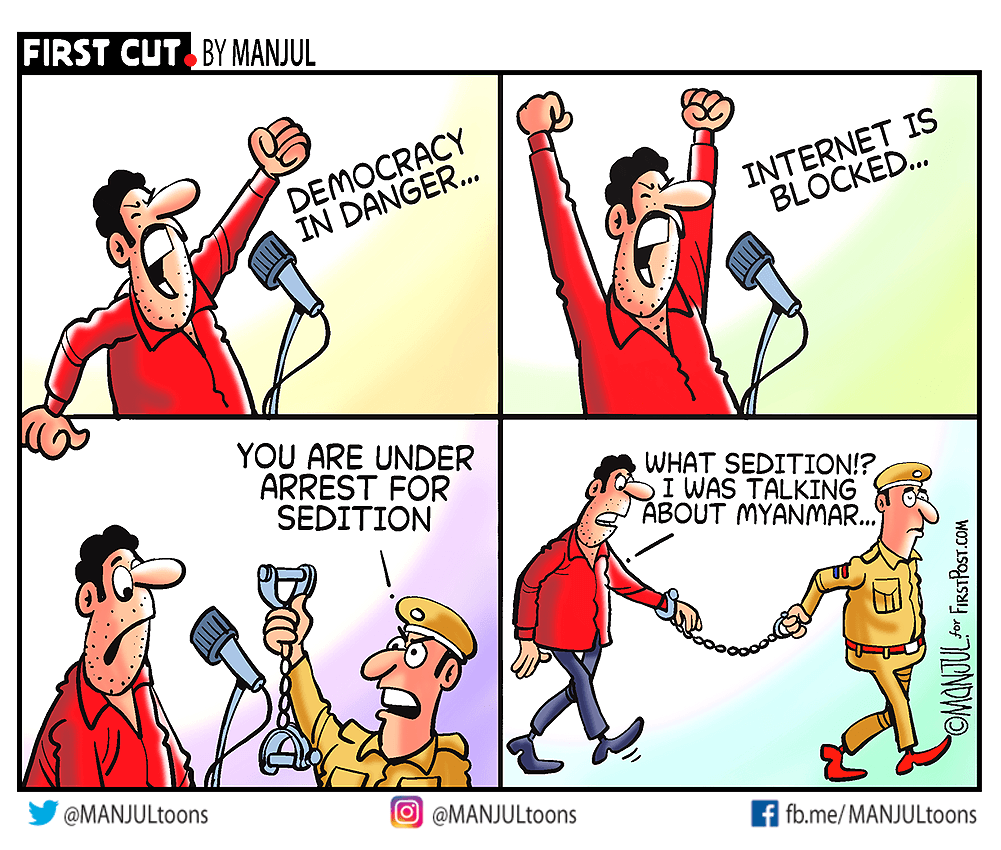

I ask this question because under our polity, the executive typically (and quite often) censors speech. Article 19(1)(a) guarantees the right to freedom of speech and expression, which can only be curtailed by a law. The laws relevant for our discussion permit only the executive or authorities appointed by it to censor speech. The June 14th order specifically refers to a) The Cinematograph Act 1952; b) The Cable Television Networks (Regulation) Act, 1995; and c) Information Technology Act, 2000. Section 4 of the Cinematograph Act empowers a board appointed by the central government to censor films. Section 5 of the Cable Television Act mandates cable operators to comply with the Programme Code, which is again enforced by the Central Government. Lastly, Section 69A of the Information Technology Act only permits a secretary-level officer of the Central Government to censor speech on the internet which does not comply with that provision.

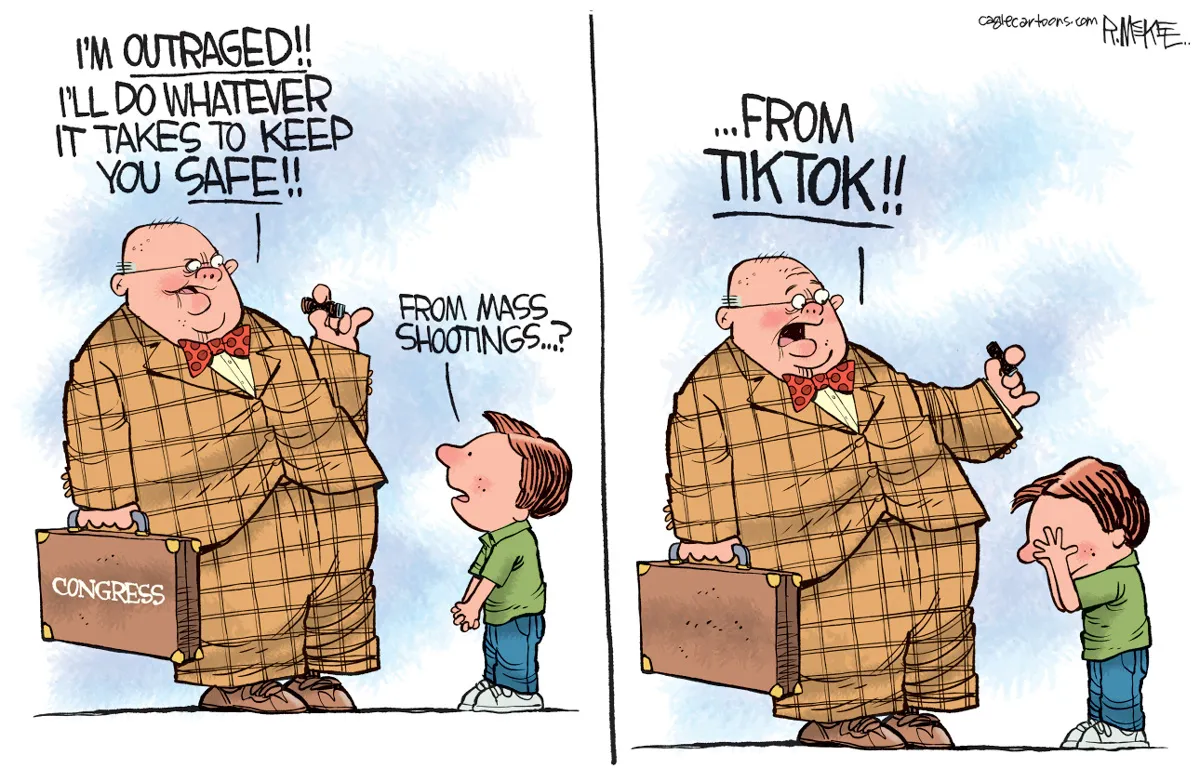

Clearly, none of the enactments mentioned above permit courts to engage in censorship. However, the argument which courts have used to censor speech is this: if statutory authorities are not censoring content even when the enactments mentioned above require them to, should the courts not interfere? Indeed, in Firaz Iqbal Khan v. Union of India, where the Supreme Court restrained Sudarshan TV from broadcasting a program which made derogatory statements against Muslims, the Court observed that it was ‘duty bound’ to ensure compliance of salutary principles of programme code. This is understandable. If courts do not intervene when statutory authorities do not perform their duties, several laws will become dead letter or worse, they will be selectively enforced based on political inclinations of those in power.

In Sudhir Kumar, the Allahabad High Court censored the documentary in question because it was of the opinion that the documentary did not comply with the enactments mentioned above. Here, the worrying aspect is how the Court decided to curtail speech.

How should courts go about censoring speech?

Each of Cinematograph Act, Cable Television Act and Information Technology Act provide a detailed procedure which must be followed before speech is curtailed. Although the processes provided are far from perfect (as there is little oversight on exercise of executive power), they do require statutory authorities to grant a hearing to content creators / publishers before censoring speech. Since these enactments do not apply to courts, they can adopt their own procedure while examining speech. Here, the process followed by the Supreme Court in Firaz Iqbal Khan provides a template.

In Firaz Iqbal Khan, the petitioner – a lawyer – approached the court in public interest seeking an injunction on the release of a series which contained several derogatory statements against Muslims. On the first hearing (August 28th, 2020), the Court refused to grant a pre-broadcast injunction. As of that date, only a trailer had been published which was not sufficient to censor Sudarshan TV. Furthermore, the Court chose to be circumspect in imposing prior restraint on publication of views. Thus, the Court issued notice to Central Government, effectively asking them to examine if the series complied with the law and listed the case for a later date.

Subsequently, Sudarshan TV proceeded to broadcast several episodes of the series. The Court examined these episodes on September 15th, 2020. On that day, the Court also benefitted from the submissions of the petitioner, Sudarshan TV and the Union Government. Based on the episodes and the submissions, the Court arrived at a prima facie conclusion that the purpose of the series was to vilify the Muslim community which violated the Programme Code which prohibited attack on religious groups. Thus, the Court injucted Suarshan TV from telecasting more episodes.

The approach of Allahbad High Court in Sudhir Kumar is starkly different from that of the Supreme Court in Firaz Iqbal Khan. In Sudhir Kumar, the Allahabad High Court censored the documentary in the first hearing. The Court did not even watch the documentary in question. The Court arrived at its conclusion that ‘evil consequences are likely to occur’ if the documentary is published, merely on the basis of averments made by the petitioner (See Paragraph 13). The Court also did not hear the counsel for Al Jazeera.

Admittedly, the Court was moved by the fact that Al Jazeera had not obtained a certificate for the broadcast of the documentary – a factual assertion confirmed by the counsel for the Union Government. Here, it is important to note that a certificate is only necessary under the Cinematograph Act before the exhibition of a film. The Cable Television Act and Information Technology Act do not require publishers to obtain prior permission of the Central Government. Al Jazeera’s documentary is not a film which will be exhibited in theatres. It is a documentary which people can watch in the comfort of their homes and it did not – and does not – require statutory approval. Yet, the Court has proceeded to temporarily injuct Al Jazeera from publishing the documentary.

This error in law certainly would not have happened if the Court was circumspect in imposing prior restrain – as the law required it to be.

Conclusion

I began this post by stating that courts in India are the sentinel on the qui vive. But as we discussed above, courts can also wear a different hat when the executive is not performing its duties under statutory enactments. In those circumstances, it is important that courts remain cognizant that their decisions can restrict a fundamental rights, which they are primarily responsible to protect. It will be interesting to see if the Allahabad High Court recognises this when the case is next heard on July 6th, 2023.

Additional Reading

- A post from Indian Constitution Law and Philosophy on Judicial Censorship, titled ‘Judicial Censorship and Judicial Evasion: The Depressing Story of Jolly LLB 2‘ (here)

- Previous post discussing how Punjab and Haryana High Court unlawfully censored speech across the world, titled ‘Punjab and Haryana High Court imagining that there’s no countries?‘ (here)