Monitoring Shutdowns – Kolhapur, Maharashtra (June 7, 2023) #2

Today, we return to the Monitoring Shutdown Series, albeit belatedly. On June 8, 2023, the internet (both, mobile data and wifi) was suspended in Kolhapur, Maharashtra and restored only after 31 hours. The internet was suspended after protestors took to the streets to demand action aginst individuals, including minors, who allegedly praised Aurangzeb and Tipu Sultan on their Instagram/WhatsApp story. The situation was particularly tense because the protestors clashed with the police. It is unclear at this stage, whether the internet was suspended by the Government of Maharashtra or by local authorities, as – again – a copy of the order is not available.

Before we examine this suspension further, it is important to record that the internet continues to remain suspended in Manipur. That shutdown began on April 27, 2023 and now 60 days have passed since citizens in Manipur have accessed the internet. This directly violates the Supreme Court’s ruling in Anuradha Bhasin v. Union of India, which held that internet shutdowns cannot be indefinite. Further, since violence continues unabated in Manipur, it is not clear if the suspension is even meeting its purported outcome of addressing the law and order situation. The only impact the suspension is an effective communication blockade in Manipur, preventing the citizens there from informing the rest of the country, about their concerns. Despite this, a vacation bench of the Supreme Court refused to hear a challenge to the shutdown stating that they did not see the urgency in the matter. A regular bench will now hear the challenge when the Court resumes after the summer holidays.

In any case, best to return to the issue at hand which is the shutdown in Kohlapur and examine whether it was imposed in accordance with the law. As is the theme in this series, my analysis will often be ‘I do not know’, demonstrating the opaque manner in which governments suspend internet services.

Procedural Compliance

- Did the concerned government publish the suspension order?

Just like the Saharanpur internet shutdown, I could not locate a copy of the suspension order either on the website of the Government of Maharashtra or the official website of District Kohlapur. Recall that as per Anuradha Bhasin v. Union of India, internet shutdown orders must be published. Although, the decision did not prescribe the mode of publication and it could be that the order was published in a local newspaper.

- Whether the order was issued under Section 5(2) of the Telegraph Act, 1885 read with Temporary Suspension of Telecom Services (Public Emergency or Public Safety) Rules, 2017?

The reporting on the shutdown uses passive voice. They state that internet has been suspended but do not mention who suspended internet services. Since, the District Administration issued prohibitory orders under Section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 to respond to the protests, it is likely that the internet was suspended under the same. Again, a copy of that order is also not available on the internet. Note that Section 144 is a general law which empowers magistrates to issue a wide-range of directions to prevent danger to human life or disturbance of public tranquility. Section 5(2) of the Telegraph Act and the 2017 Rules is a specific law. The judgment in Anuradha Bhasin (See paragraph 83), suggests (almost!) that states suspension orders should not be issued under Section 144, in view of the 2017 Rules.

- Was the order was issued by the Home Secretary?

It is likely that the order was issued by the District Magistrate.

- If the answer to 3 is no, was it issued by an officer authorised by the Home Secretary?

Not applicable.

- If the answer to 4 is yes, has the order been confirmed by the Home Secretary within 24 hours?

Not applicable.

- Was the order placed before a review committee by the next working day?

Not applicable as the order was not issued under Section 5(2) r/w the 2017 Rules. And this is precisely the problem of suspending internet services using Section 144. Not only this vastly expands the circumstances under which internet may be suspended [compare 5(2) and 144], it also prevents any review of the order.

- Did the review committee examine the order within 5 working days from the date of the order?

Not applicable.

Substantive Compliance

- Does the order contain reasons justifying suspension of internet services?

I could not locate a copy of the order.

- Whether there was a public emergency or an interest of public safety, as noted in order, justifying the issuance of the order?

The situation in Kohlapur was tense between June 7 to 9, 2023. The situation arose after protestors took to the streets to demand action aginst individuals, including minors, who allegedly praised Aurangzeb and Tipu Sultan on their Instagram/WhatsApp story. Reporting by Boomlive suggests that the protest was followed by vandalisation of properties belonging to the Muslim community. The Kohlapur police even booked 300 unidentified indivduals for damaging public property. However without further information from the ground, it is difficult to state with certainty whether the situation constituted a public emergency or a threat to the public safety. Recall that the threshhold is rather high. Public emergencies and threats to public safety are distinct from law and order concerns.

- Was it necessary or expedient to issue the order in the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign states or public order or for preventing incitement to the commission of an offence?

Again we need the order to do this analysis. We can presume that the order was issued in the interest of public order or for preventing incitement to the commission of an offence.

- Does the order adhere to the test of proportionality?

- Does it have a legitimate purpose?

The 144 order did have a legitimate purpose of preventing incitement to the commission of an offence (presumably).

- Is suspension of internet services rationally connected to fulfillment of that purpose?

I have not yet come across any research which would demonstrate that suspension of internet services addresses law and order concerns. As much sense as that makes intuitively, it not possible to determine in the hindsight if situation is in Kohlapur would have been better or worse if internet was not suspended. Here, see the discussion on Manipur, where situation has not improved despite the internet being suspended for 60 days. But for the purposes of at least this stage of the analysis, perhaps there was at least a ‘rational connection’ between the suspension and preventing incitement to the commission of an offence.

- Are there alternative measures, apart from suspending internet services, which the government could have undertaken to achieve that purpose?

Unlike the situation in Saharanpur where the administration was aware that the Gurjar community intended to take out the ‘Gaurav Yatra’, the protests in Kolhapur were sudden. The protests were followed by a clash between the protesters and the police, which also the administration could not have anticipated. Thus, the administration could have done little to prepare for the situation. Having said that, the administration could have explored alternative ways of responding to the situation on the ground. The decision to suspend internet services clearly impacted several people, some of whom took to Twitter to voice their concerns. One user highlighted how electric vehicle charging stations in Kolhapur were not working because of the suspension and advised people to go to a different district if they want to charge their cars.

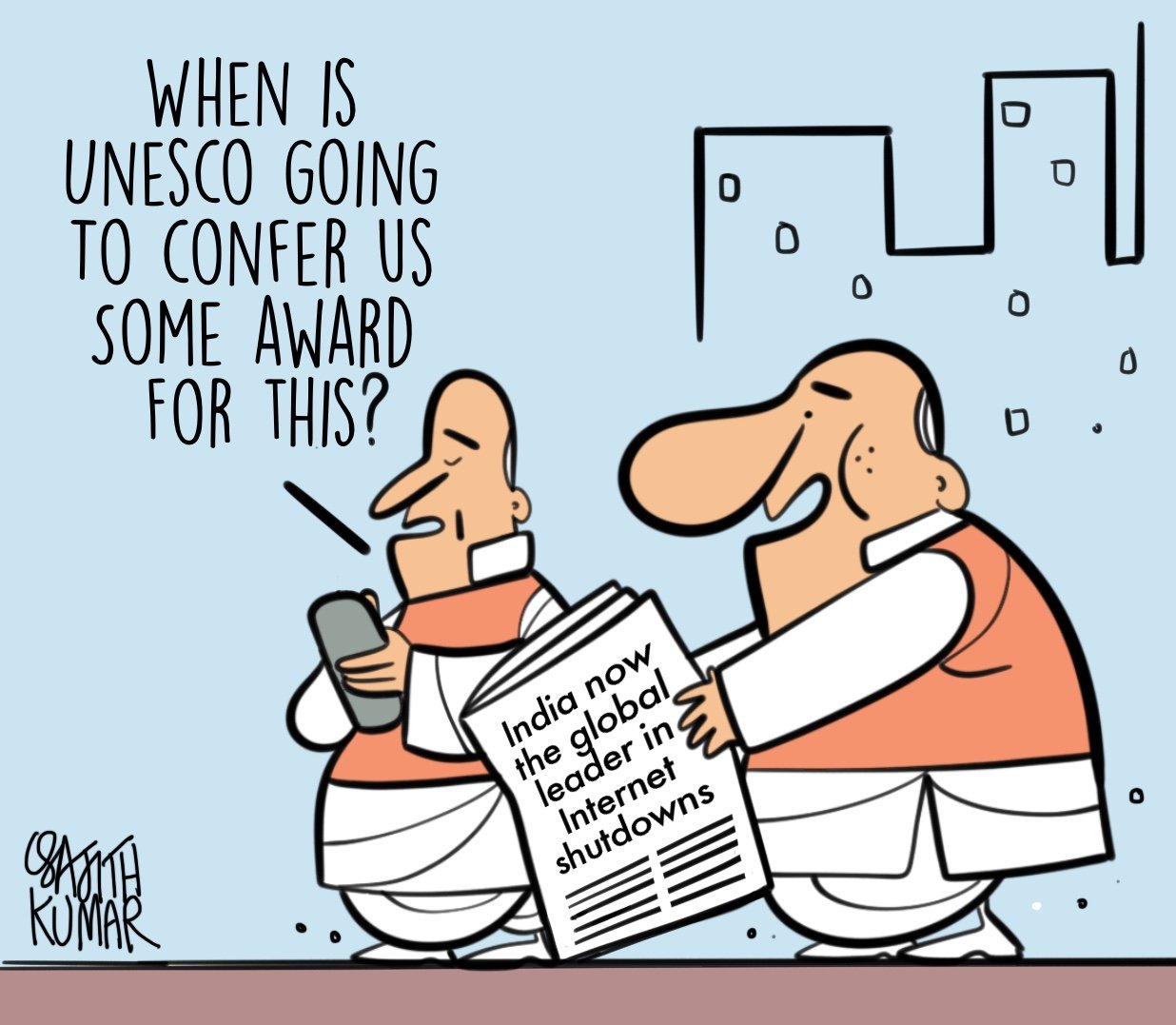

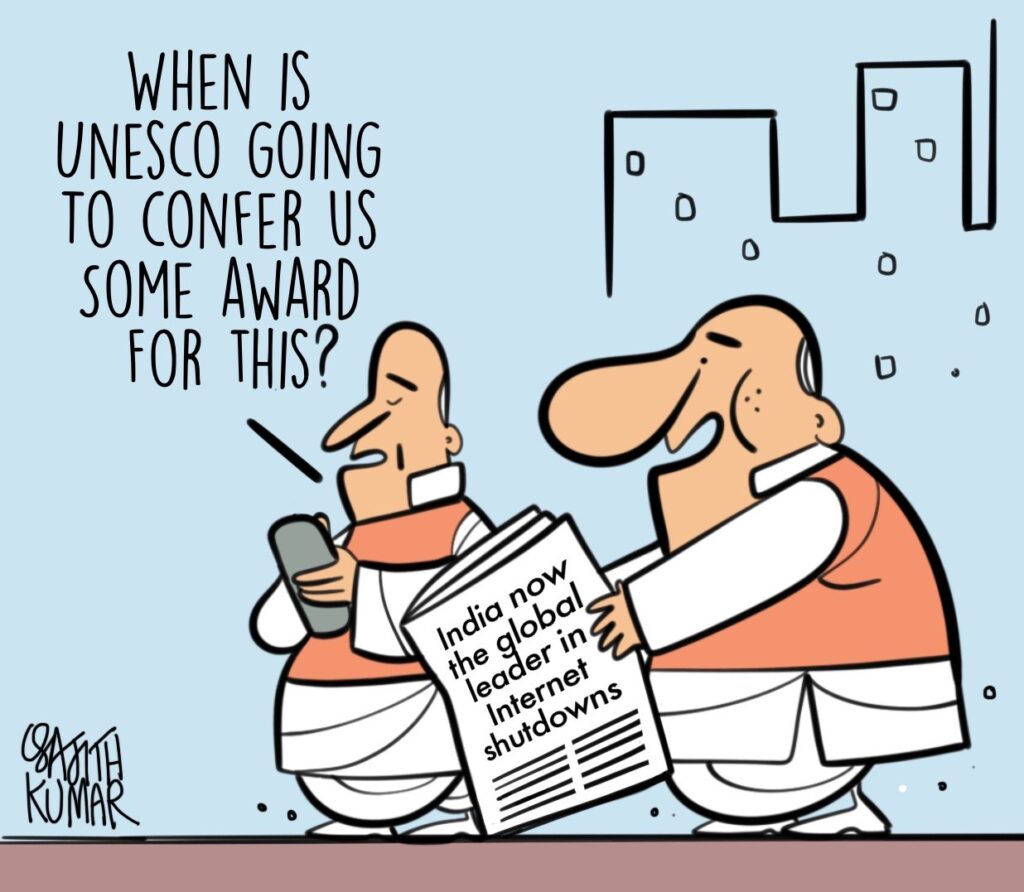

We are living in remarkable time. We may have space-age technology, but our mindset and our institutions are still in the middle-age.