Punjab and Haryana High Court imagining that there’s no countries?

In 1971, John Lennon famously asked us to imagine there’s no countries. While philosophically this is a worthwhile endeavor, it is important that Courts in India remember that their jurisdiction does not extend beyond India’s borders. The Punjab and Haryana High Court did not do so in its order dated 20.02.2023 in Court on its Own Motion v. Union of India, CROCP No. 2 of 2023. The Court relying on a previous decision of the Delhi High Court has issued directions that have a global impact.

Background is necessary. A Deputy Superintendent of Police (‘DSP’) was dismissed because he had made unpleasant remarks against the government. He approached the Punjab and Haryana High Court. While the proceedings were pending, he, along with two others, apparently circulated “malicious, libelous and derogatory videos” pertaining to those proceedings on YouTube. The Court decided that the DSP and his accomplice had committed criminal contempt of court, and directed that they be sent to prison. Further, “in order to ensure purity of justice and to protect prestige” of the Court, the Court directed the Registrar (Computerization) to prepare a list of videos the DSP and his accomplice had published and directed Facebook, Youtube, and Twitter to block/censor the videos. Pertinently for us, the Court insisted that the blocking should be global and not restricted to “geo-blocking”.

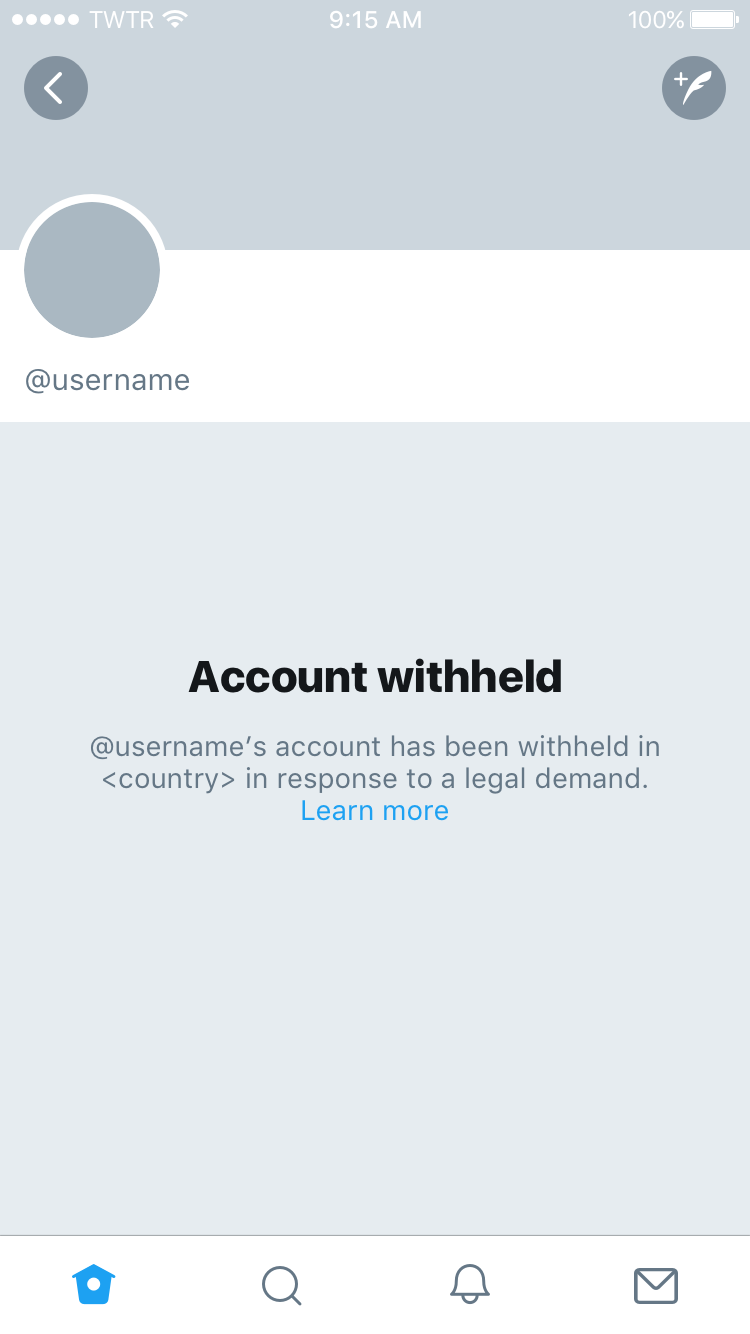

I discuss this “global takedown order” below but as an aside, Saurav Das, a journalist, somehow became collateral damage in these proceedings. Apparently, the Registrar included three Twitter posts by Saurav in the ‘List of Offending URL’s’ and shared them with the intermediaries. The tweets were critical of Amit Shah’s comments on the judiciary but importantly, they had nothing to do with the videos uploaded by the DSP or his accomplices. How Saurav’s tweets came to be included in the ‘List of Offending URLs’ remains unclear. What is clear is that censoring someone globally without hearing them, perhaps even inadvertently, does not reflect highly a Court which is insistent on ensuring “purity of justice” and protecting its “prestige”.

Coming back to the point, the Punjab and Haryana High Court directed intermediaries, Facebook, Youtube, and Twitter to globally block videos which apparently lowered the authority of the Court. There are a couple of concerns that arise because of this direction, which need to be discussed:

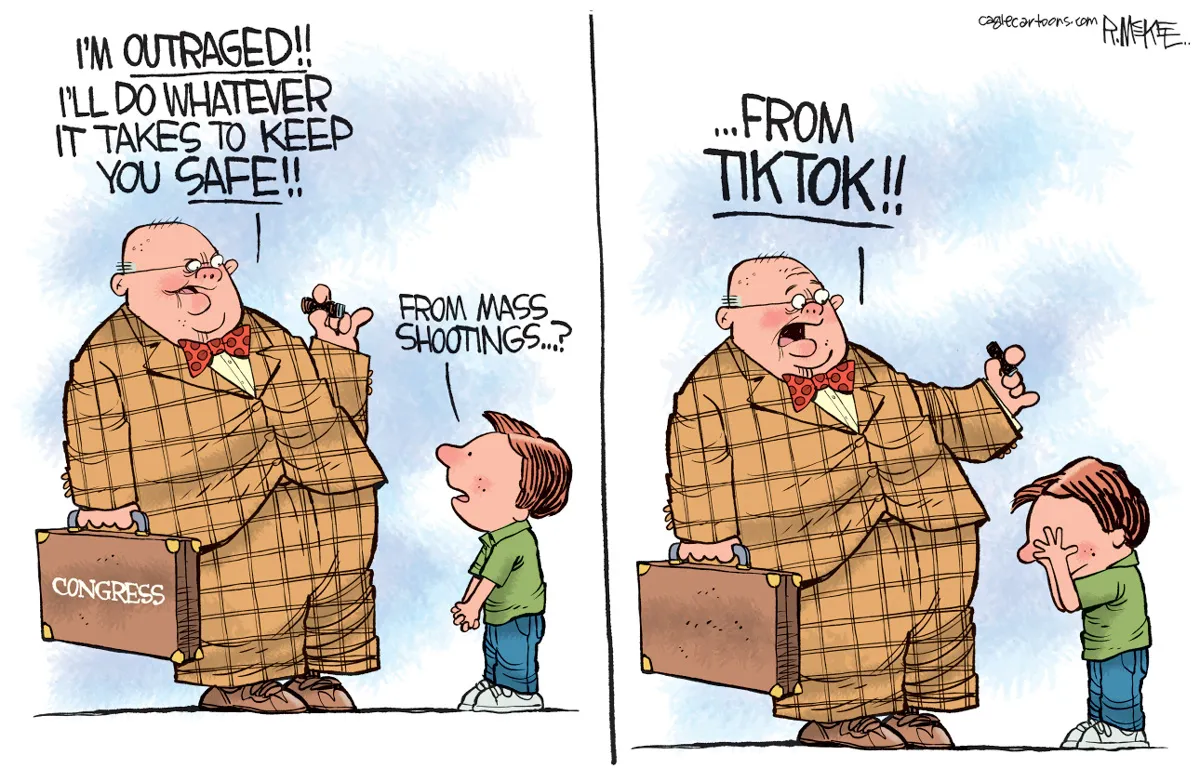

- Conflict of Laws: This is where we started. Countries have different laws, which define even similar offences, differently. The videos uploaded by the DSP may constitute contempt of Punjab and Haryana High Court but do not even constitute an offense in other countries, such as the United States of America (‘US’) which values speech. If the videos do constitute an offense in another country, the courts in that country have not arrived at this conclusion. This places the intermediaries in a spot. If you do not censor outside India, you will be held in contempt of the Punjab and Haryana High Court. If you do censor outside India, you will be exposing yourself to prosecution for censoring without a legal basis.

See Google Inc v. Equustek Solutions, where initially, the Supreme Court of Canada directed Google to de-index certain infringing websites from its worldwide search engine, and not only from google.ca. Subsequently, the US District Court of Northern California blocked the enforceability of the Supreme Court’s decision in the US on the ground that it lacked jurisdiction.

- Questionable underlying legal basis: The Punjab and Haryana High Court has relied on the decision of the Delhi High Court in Swami Ramdev & Anr. v. Facebook INC and others to issue the global takedown order. In that case, a single judge of the Delhi High Court directed intermediaries to globally take down a video that defamed Ramdev. The intermediaries have appealed the decision. While they have not been granted interim relief, a division bench of the Delhi High Court has permitted them to not comply with the single judge’s order until the case is heard finally.

In any case, the single judge’s rationale for directing global takedown was its interpretation of Section 79(3)(b) of the Information Technology Act, 2000. The provision states that when an intermediary has received actual knowledge (which must be from a Court or a Government agency, see Shreya Singhal) that any information “residing in a computer resource” controlled by it, is used to commit an “unlawful act”, the intermediary must censor that material on “that resource” or else face prosecution for that publishing that information. The single-judge opined that since the provision did not restrict itself to India, the intermediary must censor the material from every computer resource controlled by it, wherever it may be in the world. However, the single-judge should have considered that the material in question is only an “unlawful act” on servers in India and not those elsewhere in the world, as has been detailed above.

As such, the Punjab and Haryana High Court should have considered examining the law on its own instead of blindly relying on a decision, which is 1) under appeal; 2) has a questionable legal basis, and 3) the Court was not even bound by Delhi High Court’s decision.

To conclude, it is important to recognize that this is a problem that is only going to exasperate in the future. Courts in India will continue to issue global takedown orders until the position of the law is clarified by appellate courts in proceedings initiated by Ramdev. This has become a problem because most legislations (barring those related to intellectual property) do not actually empower courts to censor content. Courts are exercising their inherent powers to do so. Thus, a legislative solution demarcating what how courts can restrict speech on the internet is also necessary, lest directions by our courts affect the comity of nations.

1 Response