Supreme Court condones denying 4,00,000 citizens, the right to vote

[This post is based on a paper titled Undertrials, Voting and the Constitution, authored by Meghna Jandu and myself, which was published in the 10th edition of Indian Constitution Law Review]

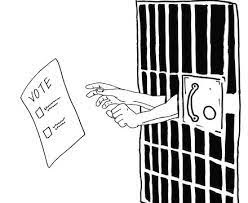

76% of prisoners in India are undertrials. They have not been convicted of any offence are in prison, and are in prison only because they have not yet been granted bail. None of these individuals, who are presumed to be innocent under the law, can exercise the right to vote. This is because of the constitutionally suspect, Section 62(5) of the Representation of People’s Act, 1951 which disqualifies every person confined in prison (civil or otherwise) from voting. The provision does not recognise that undertrials are fundamentally distinct from convicts, and should be permitted to exercise certain civil rights, especially the right to vote, which should not to be casually curtailed in any democracy.

On 4th May, 2023, the Supreme Court in Aditya Prasanna Bhattacharya v. Union of India & Ors., refused to even entertain a petition challenging the vires of this provision, despite keeping the petition pending for almost 4 years. In its judgment, the Court justified its refusal by citing its previous decisions in Mahendra Kumar Shastri v. Union of India & Anr. and Anukul Chandra Pradhan v. Union of India & Ors., which upheld Section 62(5).

In this post, I argue that the Supreme Court should have reopened the question of undertrials’ right to vote, primarily because the petitioners raised a compelling argument that was not considered by the Court in both, Mahendra Kumar and Anukul Chandra. Before we discuss the argument, it is important to recognise that the previous decisions do not themselves provide adequate justifications to uphold Section 62(5).

The faulty premise of Mahendra Kumar and Anukul Chandra

Mahendra Kumar is a paragraph-long judgment that merely states the provision ensures “purity in electing people’s representatives”, without explaining how undertrials contaminate this process.

Anukul Chandra considers every person in prison, irrespective of whether they have been convicted or not, as a class distinct from everyone not in prison. The Court’s logic is that members of the former class should be denied the right to vote as they are in prison “because of their own conduct” and thus, denying them the right achieves the legislative objective of preventing criminalisation of politics. The rationale demonstrates a fundamental concern with the reasonable classification test – the Court can incorrectly group distinct individuals in a class and then justify restrictions that could be imposed on certain members of that class but not all of them. Thus, the Court not only permits the restriction on the right to vote of convicts, who are in fact in prison “because of their own conduct”, but also of undertrials, who are a distinct class because we do not even know if they have committed a criminal offence. This important distinction has been recognised by Constitution Courts in subsequent cases where undertrials in prison have been permitted to contest elections, but this right has not been extended to convicts.Thus, the law today, rather incongruously, is that undertrials in lawful custody can contest elections but cannot exercise their right to vote.

In view of the above, both, Mahendra Kumar and Anukul Chandra, are based on a unsound premise that everyone in prison is a criminal. The Supreme Court last week should have recognised this.

The Petitioner’s compelling argument

As mentioned above, the Petitioner in Aditya Prasanna Bhattacharya challenged Section 62(5) on a ground not considered by the Supreme Court in both previous decisions. According to reporting by LiveLaw, the Petitioner contended that the right to vote can only be curtailed in accordance with Article 326 of the Constitution, which exhaustively lists the permissible grounds. These grounds are non-residence, unsoundness of mind, crime, or corrupt or illegal practice.

Article 326: The elections to the House of the People and to the Legislative Assembly of every State shall be on the basis of adult suffrage. – The elections to the House of the People and to the Legislative Assembly of every State shall be on the basis of adult suffrage; that is to say, every person who is a citizen of India and who is not less than eighteen years of age on such date as may be fixed in that behalf by or under any law made by the appropriate Legislature and is not otherwise disqualified under this Constitution or any law made by the appropriate Legislature on the ground of non-residence, unsoundness of mind, crime or corrupt or illegal practice, shall be entitled to be registered as a voter at any such election. [Emphasis supplied]

This is a compelling argument because a literal interpretation of Article 326 suggests that the existence of the grounds on which the right to vote may be curtailed is a condition precedent to the disqualification. Therefore, if a citizen is of unsound mind, they can be disqualified from voting through a law. However, the law enabling such disqualification will not be permitted under Article 326 if the law disqualifies a citizen even before unsoundness of mind is proven. The legislature, hence, can disqualify citizens from voting only if any one of the grounds mentioned under Article 326 is proven against such citizens. If citizens could be disqualified from voting on a mere suspicion that they fall within one of the grounds mentioned under Article 326, even laws that disqualify citizens who are alleged of having an unsound mind or have an FIR registered against them, will be permitted under Article 326.

This interpretation is consistent with how Constituent Assembly viewed Article 326. During the debates on Draft Article 67(6) [later adopted as Article 326] on 8th January 1949, Dr. B.R Ambedkar stated that according to this article, “the commission of a crime is not by itself any disqualification. The disqualification is only when a person is punished and detained in imprisonment. It is during the period of imprisonment that he loses the right to vote.” Thus, punishment is indeed a necessary condition before disqualification. Section 62(5) does not recognise this, and fatally disqualifies everyone in prison, even when they have not been punished.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court in Aditya Prasanna Bhattacharya should have recognised the concerns mentioned above, especially since they were brought to its notice. Beyond this, considering recent jurisprudence, it was also important that the Court test Section 62(5) on proportionality – an aspect not considered by this post but is an analysis that should be carried out. Lastly, it is important to note that the Court has recently not been hesitant in reopening the seemingly settled position of law in order to further constitutional intent. In S.G Vombatkare v. Union of India, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court “put in abeyance” Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 which was upheld by a five-judge bench Kedar Nath Singh v. State of Bihar. Thus, a precedent from the past is not set in stone. Unmindful reliance on precedent in Aditya Prasanna Bhattacharya does not recognize the grimness of denying almost 4,00,000 innocent individuals, the right to vote.